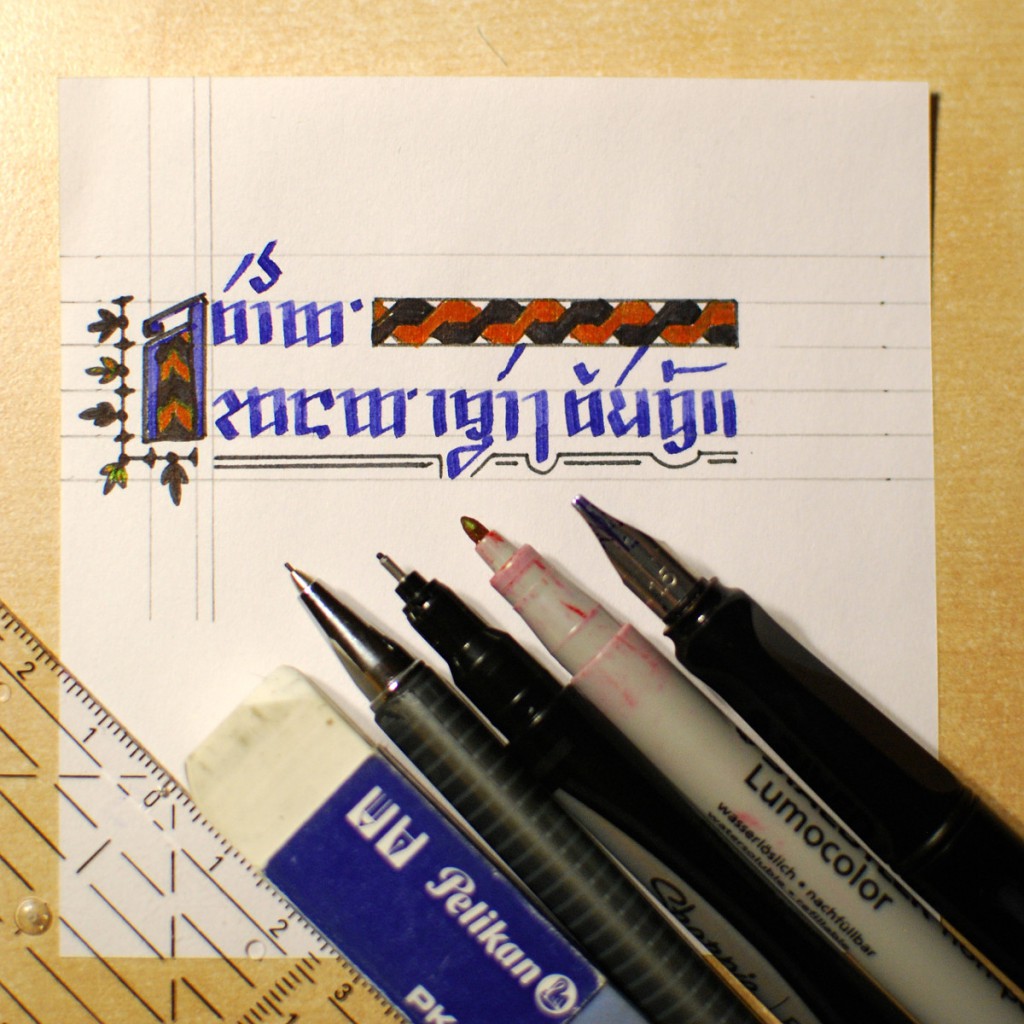

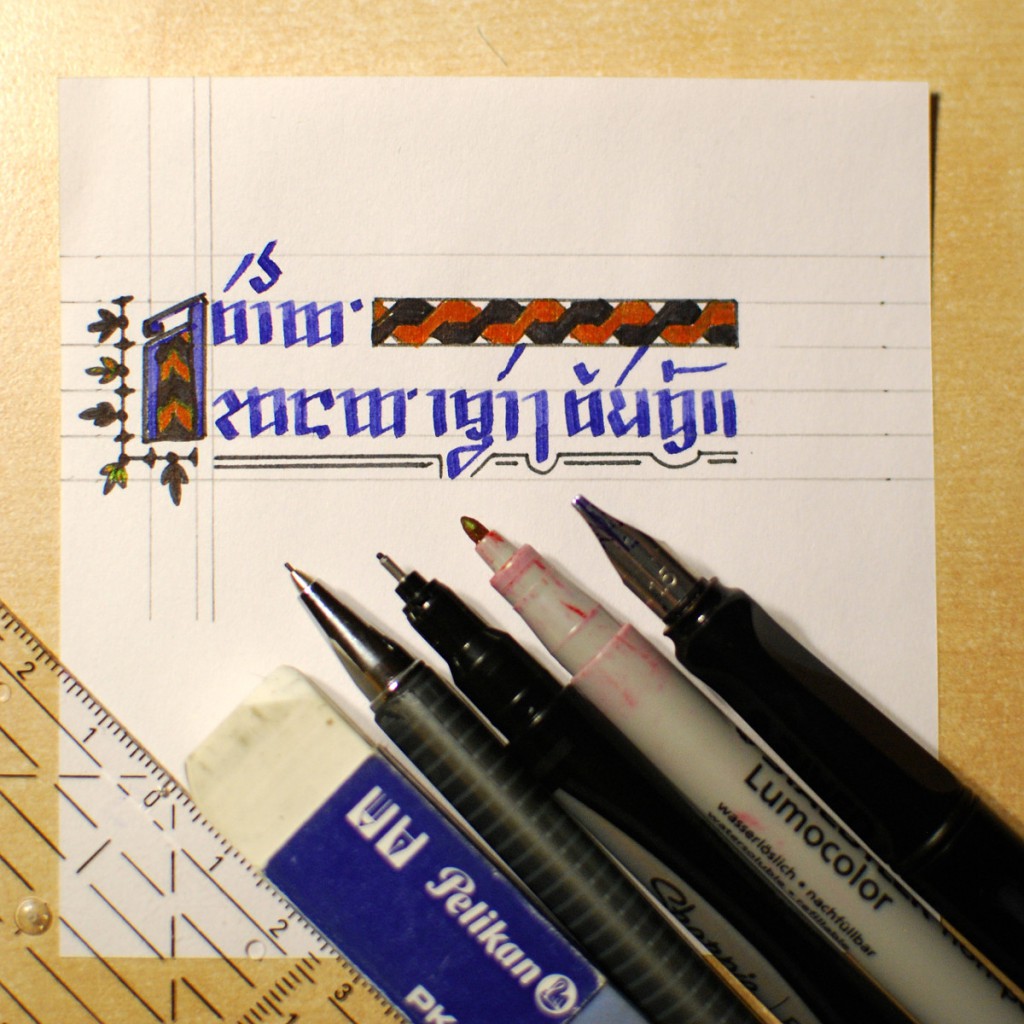

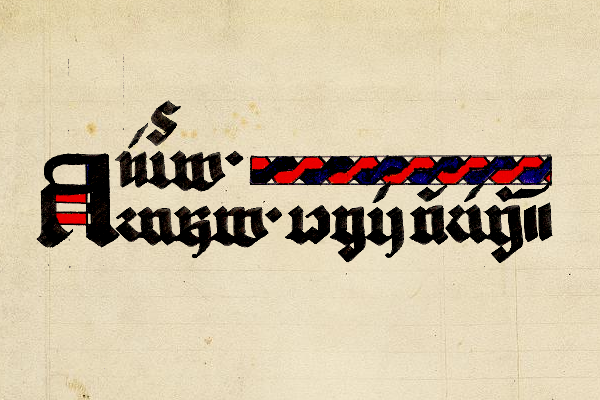

I’m a doodler. More specifically, I’m in the habit of doodling random words and sentences when watching TV. Moreover, ever since I started toying with adapting Ayeri’s Tahano Hikamu writing system to a style that resembles blackletter, that idea hasn’t let go of me, and it’s become part of my idle doodling. I briefly mentioned the idea of a blackletter-style Tahano Hikamu in the grammar (p. 61–62) along with a small example, but I’ve never really documented it seriously.

So, blackletter. What does this have to do with Ayeri, since it undeniably takes some of its aesthetic of sound and spelling not from European languages but rather from southeast Asian languages? And what’s more, its ‘native’ writing system does so as well—maybe even turning some of the features of real-world syllabic alphabets typical of that region up to eleven. On the other hand, so-called Gothic scripts (see e.g. Knight 1996: 320–322, or if you read German, Schneider 2014: 28–85; this is not directly related to the Gothic language and its alphabet) are a western-central European variation of the Latin alphabet which came into fashion in the middle ages. They survive in the shape of blackletter print for certain purposes up to the present day.

Here in Germany at least (and no doubt in other parts of the Germanic-speaking world as well), you can still find blackletter typefaces for instance in the mastheads of newspapers, on pub signs, beer labels, and other things that are supposed to evoke either a long-standing tradition or rustic folklore. Unfortunately, blackletter also has a dark side: it is also associated with the Nazi era and continues to be used in connection to fascist, nationalist, and racist ideas. In my exploration of and toying with this style, I expressly distance myself from such ideologies.

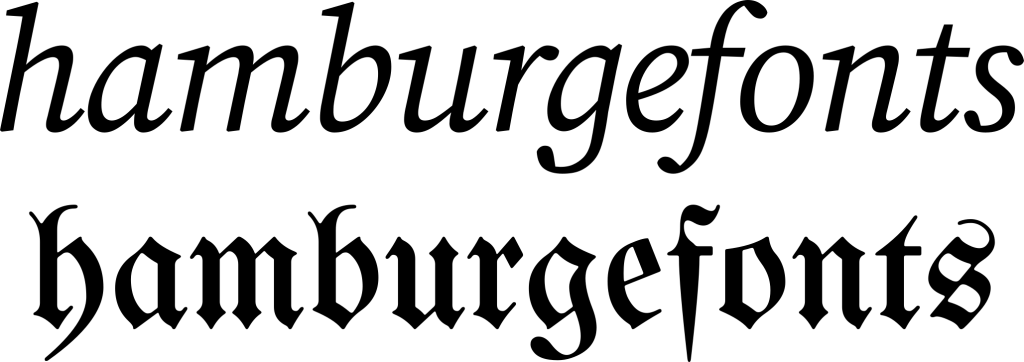

One key characteristic of Gothic scripts—of which blackletter typefaces are a variant—is that they emphasize vertical lines, making characters tall and narrow, like the windows in Gothic cathedrals. Another one is that the round parts of letters are broken up into multiple strokes, with the ‘feet’ of stems typically bent to the right (Schneider 2014: 29). According to Schneider (2014: 28–29) ‘gothification’ of the Carolingian minuscule can be observed first in the Anglo-Norman area, i.e. England and northern France, and also in Belgium in the late 11th and early 12th century. She writes that the style then made its way into central Europe from the mid-12th century on, spreading from west to east. Gothic book hands and blackletter typefaces with their intricate joining together of angles, straight and curved lines, and sometimes even added embellishing hairlines and tittles may lead to very intricate, at times playful shapes in spite of a stout overall look.

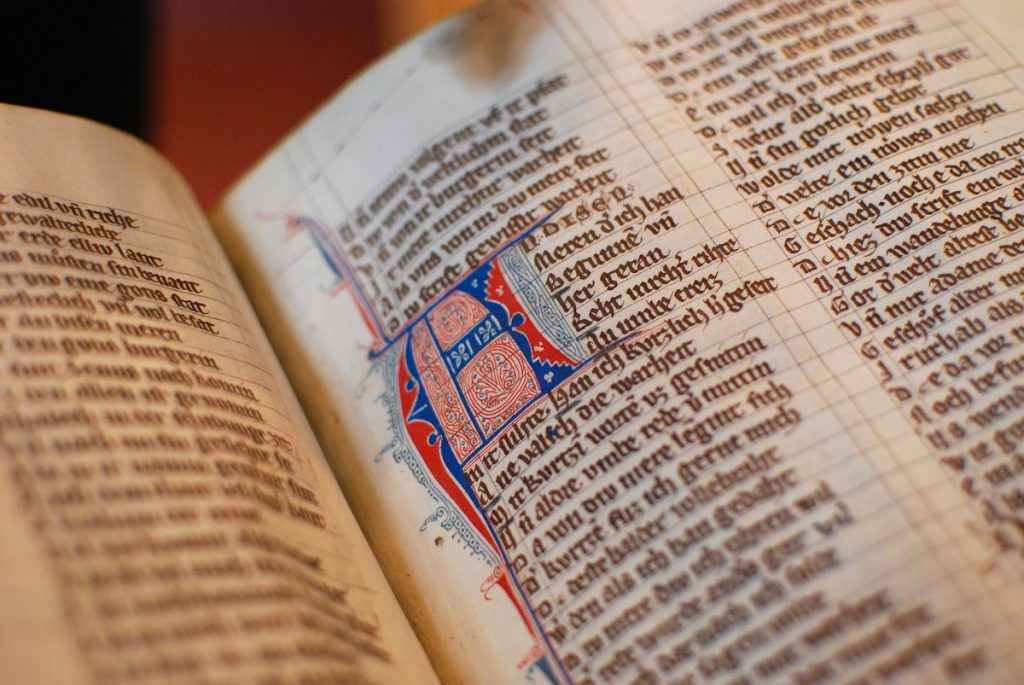

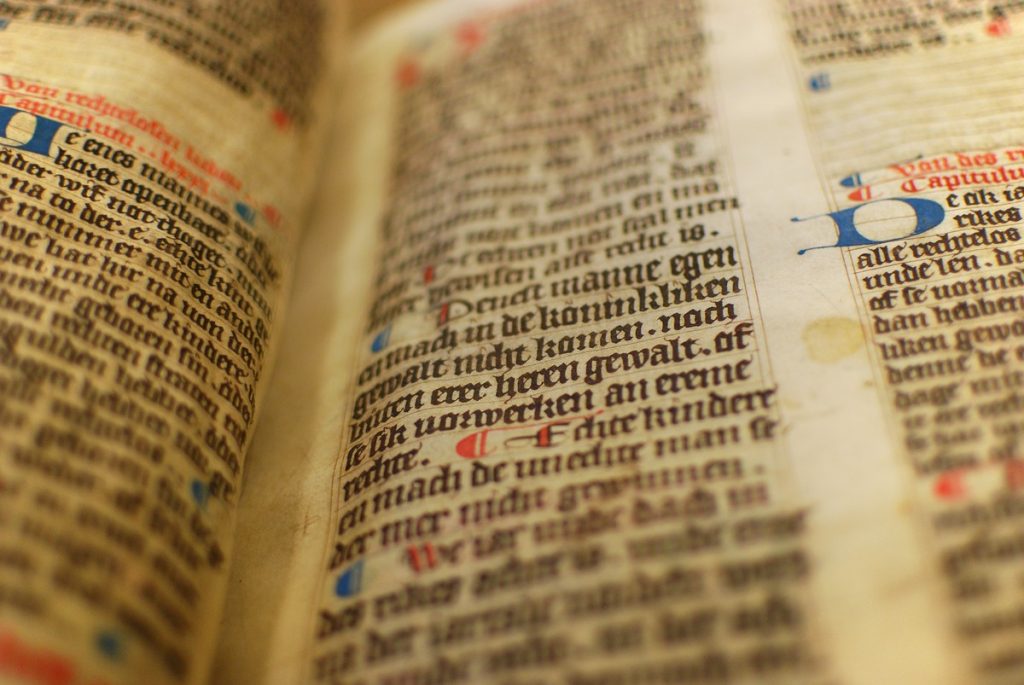

What brought me to combine two such disparate things as Gothic scripts and Ayeri’s writing system, anyway? For one, I’ve been working for the Handschriftencensus research project for the past few years. Handschriftencensus is a meta-catalog on the transmission of all medieval texts in German language by way of manuscripts. In real-life small talk, I like to say it’s basically the Yellow Pages of German codicology research. At the office, we don’t work with old codices directly, however, one of the pre-pandemic perks my job included was participating in excursions to and workshops at libraries such as the Heidelberg University Library’s historical collection and to get literally hands-on with old books there. When not traveling, digitized manuscripts have to suffice. Looking at writing from several hundred years ago is thus part of my current job, and I can’t deny that manuscripts hold some fascination for me, as the photos in this article probably suggest.

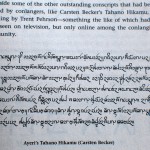

Secondly, I’ve long found southeast Asian scripts such as Balinese, Burmese, Javanese, Khmer, Thai, etc. intriguing both regarding their system of writing and their look, which also had an influence on Tahano Hikamu. Several years ago, I stumbled upon an image on Wikipedia of the title plate of an 1898 book commemorating queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands’ accession to the throne in 1890. The issue of European colonialism (again, with its history of violence, exploitation, and lingering socioeconomic problems) aside, what especially caught my intrigue here is the first line, which combines Javanese writing with the European blackletter style.

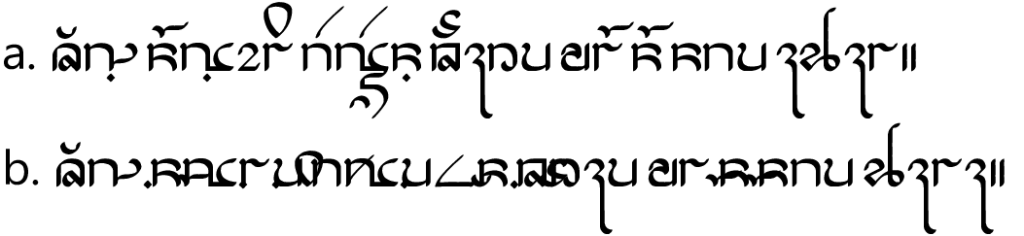

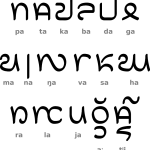

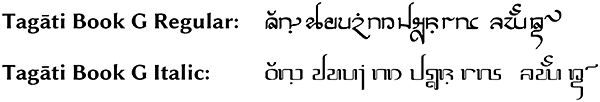

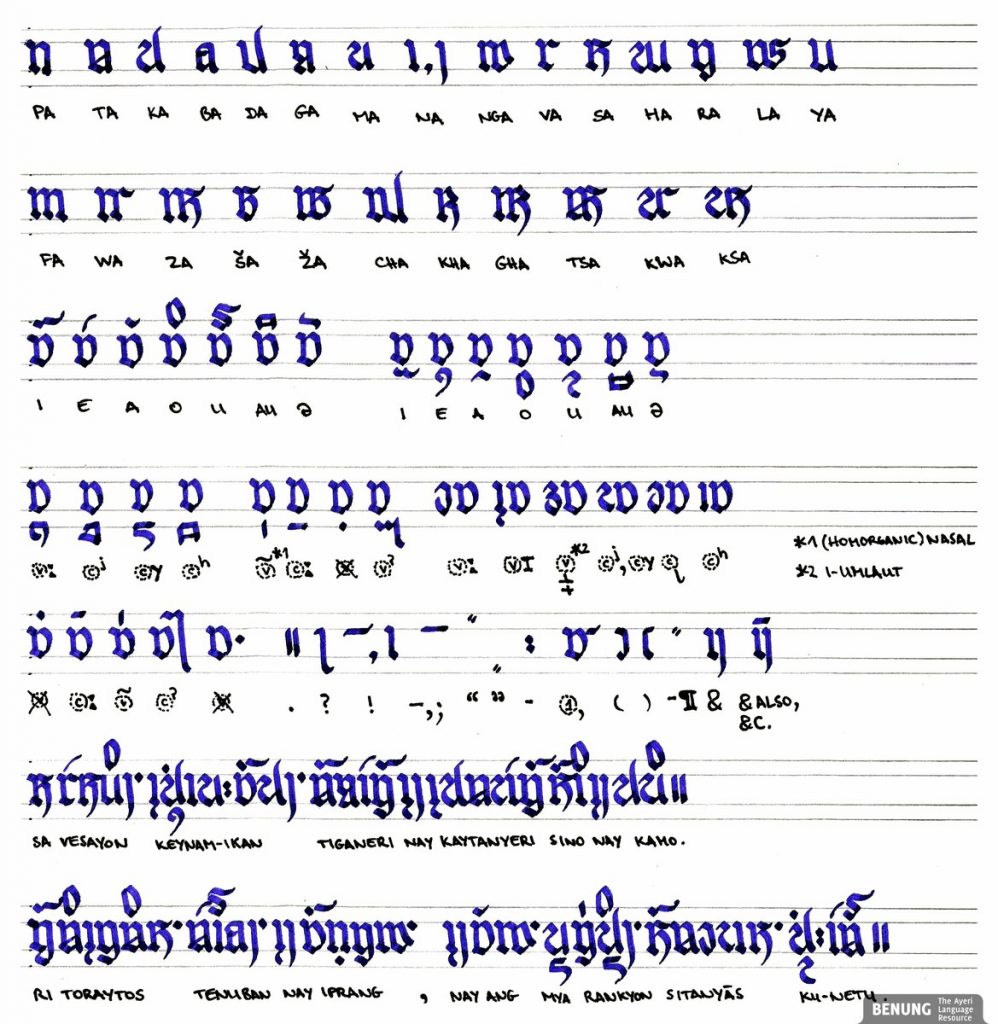

Both the Latin alphabet and the Javanese script emphasize the vertical axis, which opens up a possibility for stylistic experimentation with Gothic style features in an alien environment. If something like this is possible, shouldn’t it also be possible in my script? Tahano Hikamu’s consonant letters as well are mainly built on a lattice of vertical strokes, so there shouldn’t be a problem either to adapt them to broken lines and curly feet. In some cases, it proved even possible to adapt the shape of Latin letters to the ‘gothicized’ Ayeri script directly. The following chart gives an overview of the characters and diacritics with the exception of numerals, which I’ve so far neglected to experiment on.

The following correspondences exist, in some cases also independent of the particular style of Tahano Hikamu:

- TH

pa — Lat. n

pa — Lat. n - TH

ba — Lat. a (double-storey shape)

ba — Lat. a (double-storey shape) - TH

na — Lat. i, j

na — Lat. i, j - TH

nga — similar to Lat. w

nga — similar to Lat. w - TH

va — Lat. r

va — Lat. r - TH

ra — similar to Lat. g (looptail shape)

ra — similar to Lat. g (looptail shape) - TH

ya — Lat. u

ya — Lat. u - TH

fa — Lat. m

fa — Lat. m - TH

sha — similar to Lat. B

sha — similar to Lat. B - TH

kha — similar to Lat. R

kha — similar to Lat. R

The diphthong marker ![]() appears turned on its head in the above chart (4th line, 5th item from the right), resulting in what looks similar to the quarter rest in music. This is a stylistic variation I have recently experimented with, in part also because I keep forgetting preposed diacritics when doodling words as described initially. Starting with a base stroke thus often rescues the attempt to write a word, so it’s a beneficial feature to keep. The basic grapheme in its ‘canonical’ orientation is straightforward enough to be adapted as well, though. The letter

appears turned on its head in the above chart (4th line, 5th item from the right), resulting in what looks similar to the quarter rest in music. This is a stylistic variation I have recently experimented with, in part also because I keep forgetting preposed diacritics when doodling words as described initially. Starting with a base stroke thus often rescues the attempt to write a word, so it’s a beneficial feature to keep. The basic grapheme in its ‘canonical’ orientation is straightforward enough to be adapted as well, though. The letter ![]() ga posed the greatest challenge, similar to Latin g, which itself has invited stylistic experiments by both scribes and typographers over the centuries as well. For instance, look at the gs in James Todd’s (2015) article on designing the Essonnes typeface, which he samples from a version of the classic Didot. Aren’t they glorious with their serifed lower bowls?

ga posed the greatest challenge, similar to Latin g, which itself has invited stylistic experiments by both scribes and typographers over the centuries as well. For instance, look at the gs in James Todd’s (2015) article on designing the Essonnes typeface, which he samples from a version of the classic Didot. Aren’t they glorious with their serifed lower bowls?

Will you see more of Ayeri written in this style, maybe even a cohesive text? Frankly, I have no idea what the future holds, since I’m still working on my dissertation and am intent on finishing it this year. Small indulgences like writing this blog article already leave me with a slightly bad conscience about neglecting my off-hour duties (working on your PhD is usually an unpaid hobby in German academia, at least in the humanities, and yes, people are not happy about it).

Suffice it to say, doodling in this style has renewed my appreciation for the toil of medieval scribes. It’s a slow and arduous way of writing if you want it to look good, even when it’s just to write a few lines.

- Knight, Stan. 1996. The Roman Alphabet. In The World’s Writing Systems, edited by Peter T. Daniels and William Bright. New York, NY, and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 312–332.

- Koninklijk Huisarchief. 2013. Book title commemorating Wilhelmina’s ascension, Semarang 1898. Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain). [Link]

- Schneider, Karin. 2014. Paläographie und Handschriftenkunde für Germanisten: Eine Einführung. 3rd ed. Sammlung kurzer Grammatiken germanischer Dialekte, B. Ergänzungsreihe 8. Berlin and Boston, MA: de Gruyter. DOI: 10.1515/9783110338676.

- Todd, James. 2015. Making Fonts: Essonnes. I Love Typography (June 12). [Link]

- Heidelberg, University Library, Cod. Pal. germ. 167. [Heidelberg Univ. Lib.; HSC]

- St. Gallen, Cantonal Library, Vadian Collection, VadSlg Ms. 302. [e-codices; HSC]