I had been working on a Ph. D. in German Language since what feels like forever—more accurately, since February of 2017. As the proverb goes, “Good things come to those who wait,” so last month, the revised version of my thesis has finally been published by Language Science Press’ Advances in Historical Linguistics series.

Carsten Becker. 2024. Genusresolution bei mittelhochdeutsch beide: Eine Analyse im Rahmen der Lexical-Functional Grammar (Advances in Historical Linguistics 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10451456 (🔓). [Worldcat]

LangSci was my first shot at submitting my thesis to a publisher at the suggestion of both a colleague-friend and my supervisor, so I’m beyond happy this worked out and my baby found a home in this newly formed series. It now even happens to be its initial volume, and I hope to fill those shoes adequately, what with setting the tone, first impressions etc. etc. May many other interesting books follow!

Since my thesis is published now in fulfillment of the one remaining requirement for the degree Dr. phil., today, I was able to pick up my diploma from University of Marburg’s Department of German Studies and Arts at long last, after having passed my defense already in September 2022 (that’s common procedure in Germany, unknown to most). Working on my thesis cost me lots of dedication and some nerves over the years, a few thousand hours of mostly my spare time certainly, and it’s like an era of my life has come to an end. Even though it’s certainly an achievement, being done still feels a little unreal. After all, you’re never really done while riding the academic rollercoaster.

What’s the book about?

The book’s title translates to English as “Gender resolution of Middle High German beide [‘both’]: A Lexical-functional Grammar based analysis.” For the purpose of this blog post, I will only scratch the surface of what the main title entails. I suppose that alone needs enough unpacking, so let’s look at some backgrounds first.

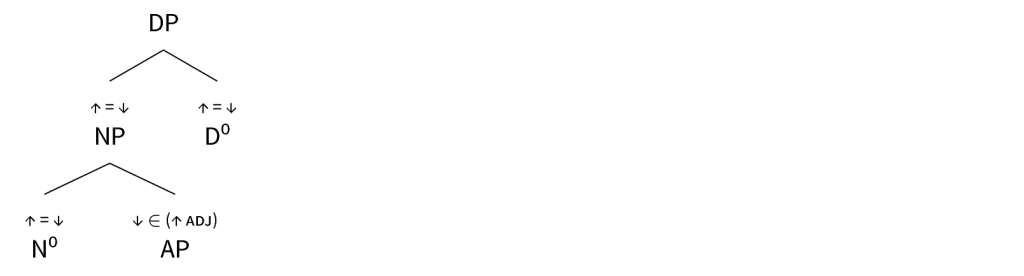

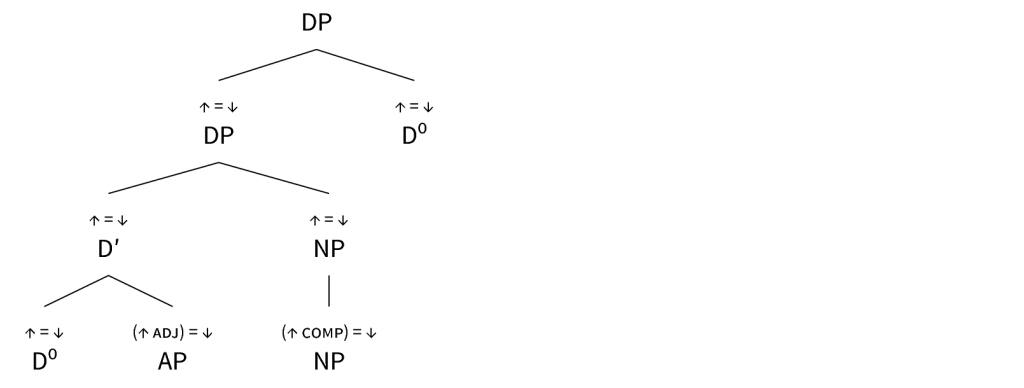

German infamously inflects the definite articles of nouns for case, number, and gender: der, die, das, den, dem, des. But it doesn’t stop there—oh nein! It also declines its attributive adjectives for those categories. Adjective declension extends to other kinds of noun modifiers as well, for instance, determining quantifiers like beide ‘both’. In today’s German, the nominative and accusative cases feature only one plural marker in the adjective declension’s strong (ST) paradigm for all of its three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. This marker is -e, exemplified in (1) by the adjective gut ‘good’.

-

- gut-e Männer

good-NOM.PL.ST men[M]

‘good men’ - gut-e Frauen

good-NOM.PL.ST women[F]

‘good women’ - gut-e Kinder

good-NOM.PL.ST children[N]

‘good children’

- gut-e Männer

That hasn’t always been the case, however. In Old High German (c. 750–1050 CE; Braune & Heidermanns 2023; Schmid 2023)—Old English’s West Germanic cousin from the hilly and mountainous regions in central Europe that underwent the accordingly-named High German Consonant Shift—all three genders were distinguished in the plural, as (2) illustrates: -e /e/ for masculines, -o /o/ for feminines, and -iu /iu̯/ for neuters.

-

- guot-e man

good-NOM.PL.M.ST men[M]

‘good men’ - guot-o frouwūn

good-NOM.PL.F.ST ladies[F]

‘good ladies’ - guot-iu wīb

good-NOM.PL.N.ST women[N]

‘good women’

- guot-e man

A few centuries later, in the Upper German subgroup of Middle High German (MHG, c. 1050–1350 CE; Paul et al. 2007; Klein et al. 2009, 2018), there still used to be a distinction between masculine–feminine -e /ə/ and neuter -iu /yː/. That is, in agreement morphology, references to grammatically masculine or feminine referents in MHG are usually marked by the masculine–feminine form, so it’s guote ‘good’ which occurs in (3a–b) in relation to both man ‘men’ and vrouwen ‘ladies’. (Note that when I stick to the term MHG for brevity in the following, I’m referring only to Upper German of that period.)

-

- guot-e man

good-NOM.PL.M+F.ST men[M]

‘good men’ - guot-e vrouwen

good-NOM.PL.M+F.ST ladies[F]

‘good ladies’ - guot-iu wīp

good-NOM.PL.N.ST women[N]

‘good women’

- guot-e man

Tangentially, but not so tangentially, the word wīb, wīp ‘woman’ in (2c) and (3c) is a notable lexical exception to the principle of correspondence between the conceptually associated social gender of a person-noun and grammatical gender: it denotes a female person in its semantics, but formally, that is, in terms of morphology, it’s neuter instead of feminine, like the famous Mädchen ‘girl’ (but also see wife!). Thus, you’ll usually find guotiu ‘good’ in this context. Anaphoric reference by pronouns, however, quickly switches to feminine in accordance with the (adult-)female semantics very typically. That is, you’ll normally find si ‘she’ in reference to wīp ‘woman’ rather than eʒ ‘it’.

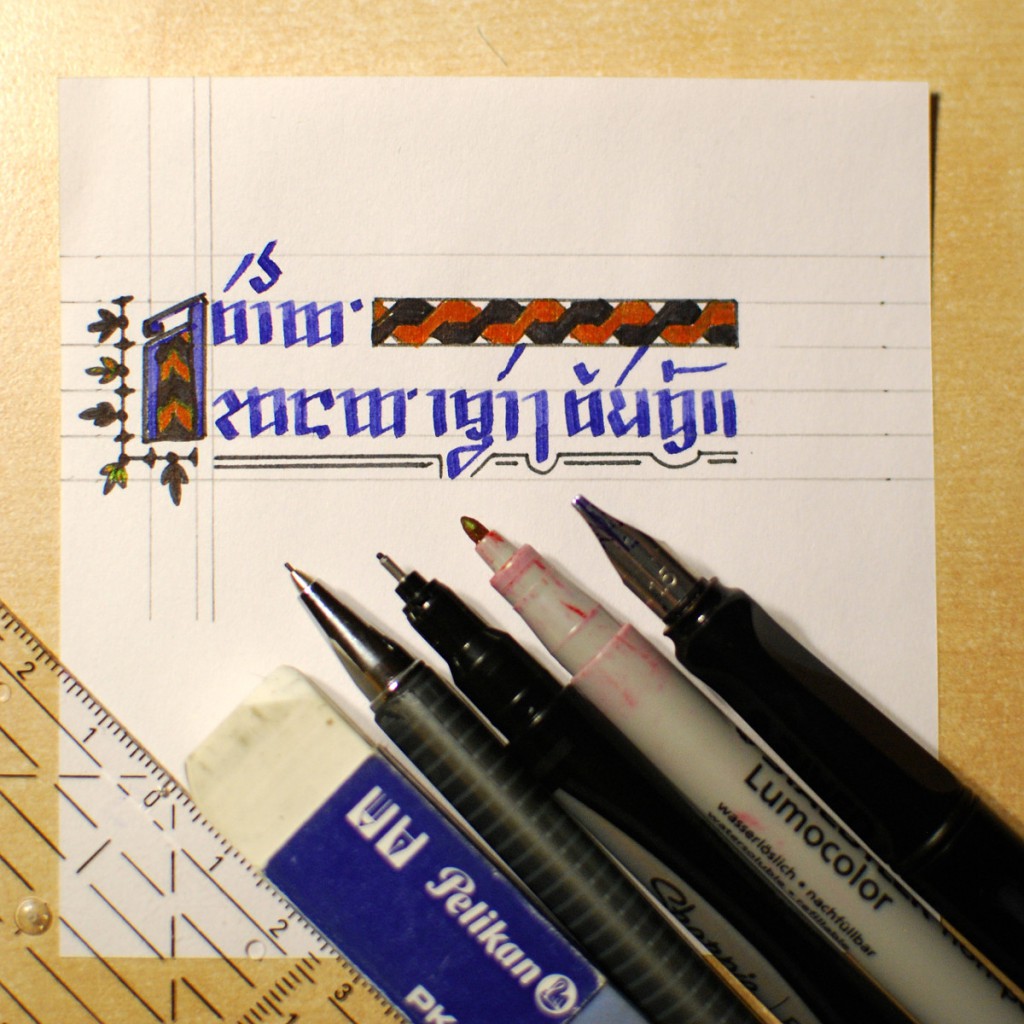

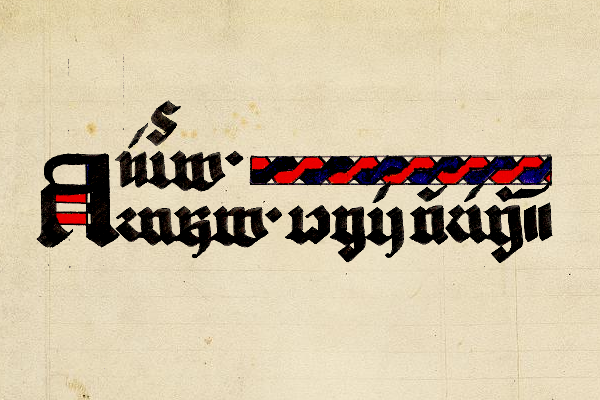

The prologue of the Nibelungenlied provides a prominent example along those lines. See how in (4) even the adjective sc[h]œne ‘beautiful’ displays the feminine form in spite of being an attribute of neuter wīp ‘woman’. This is formally ungrammatical and as far as I can tell not the most typical usage—neuter schœneʒ would be expected—but it nicely highlights how semantics can have a strong effect on gender agreement even in written texts.

- Ez wuohs in Búrgónden ein vil édel magedîn, daz in allen landen niht schœners mohte sîn, Kriemhilt geheizen: si wart ein scœne [sic] wîp.

it grew in Burgundy a much noble girl[N] that in all lands not of.more.beauty could be Kriemhilt[F] named 3SG.F.NOM became a beautiful-ACC.SG.F.ST woman[N]

‘In Burgundy, a young noblewoman was growing up [such] that nothing more fair could be found in any of the lands, Kriemhild by name: she became a beautiful woman’ (Nibelungenlied 2:1–3; de Boor & Wisniewski 1988: 3, after manuscripts A and B)

Now let’s get to the heart of my survey: What about mixed-gender reference to a man and a woman simultaneously? Since -e marks both masculine and feminine reference in MHG in the strong nominative and accusative plural, you might expect e-forms in combined cases as well. And if you’ve ever studied a Romance language you may remember the rule that as soon as one man joins an all-female group, the whole group will be treated as grammatically masculine. Well—not so here! In cases of mixed-gender animate reference, we can frequently observe neuter forms instead as a kind of fall-back strategy based on semantics rather than morphology.

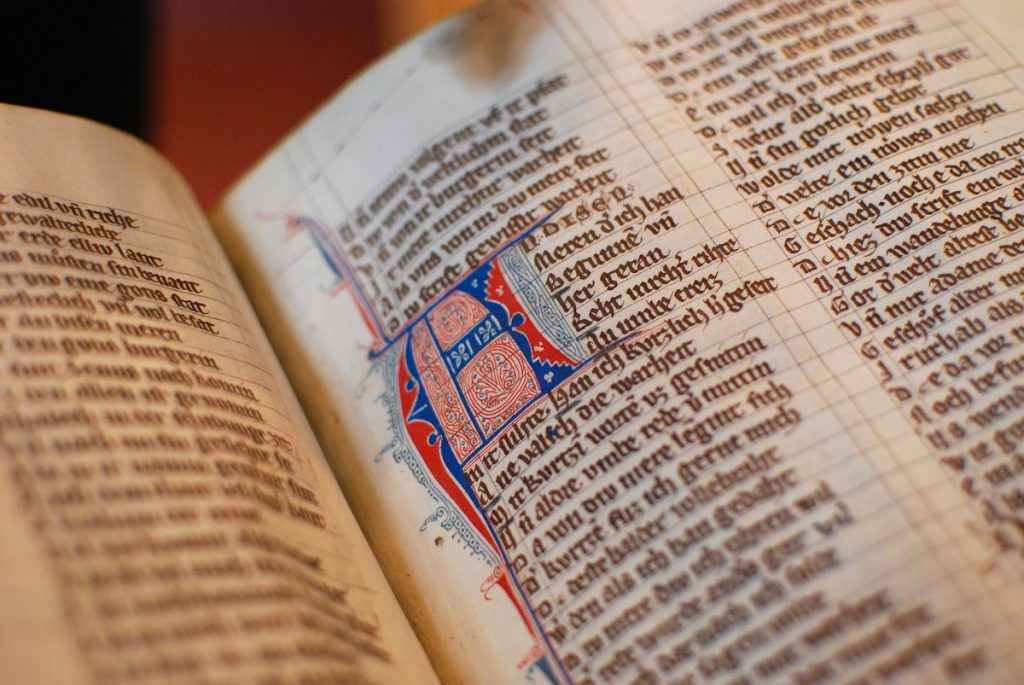

An example of this phenomenon from my data is given in (5). Observe the neuter form beidev ‘both’, ultimately relating to Ulrich and Elsbeth, a heterosexual couple. (Funny spellings are due to quoting from historical sources verbatim. Note that the letters u and v were still used interchangeably at the time, as were i and j. The letter ſ is a historical variant of s.)

- vlrich vnd frow Elzbet […] diſen prief / den ſi beidev habent gebeten ze ſchriben

Ulrich[M] and Mrs. Elsbeth[F] […] this charter that 3PL.NOM both-NOM.PL.N.ST have asked to write

‘Ulrich and Mrs. Elsbeth […] this charter that they both have asked to write’ (Wilhelm et al. 1932–2004: 4,176:26–27; No. 2843, Salzburg, 1297; photo)

Neuter is also what appeared in my data for inanimates, very regularly independent of any combinations of grammatical gender, as in (6a) with masculine Hof ‘farm’ and feminine Mule ‘mill’, and in (6b) with all-masculine zehenden ‘tithe’ and Garten ‘garden’.

-

- den Hof […] vnd di Mule / di er paidev […] hot

DEF.ACC.SG.M farm[M] […] and DEF.ACC.SG.F mill[F] REL.ACC.PL he both-ACC.PL.N.ST […] has

‘the farm […] and the mill that he both has […]’ (Wilhelm et al. 1932–2004: 3,254:35–37; No. 2011, Seitenstetten, Amstetten district, 1294; photo) - vnſerne zehenden […] vnde ainen Garten […] div wier baidiv fvr reht aigen her haigen braht

our-ACC.SG.M.ST tithe[M] […] and a-ACC.SG.M.ST garden[M] […] REL.ACC.PL.N we both-ACC.PL.N.ST for rightful property here have brought

‘our tithe […] and a garden […] that we [i.e. three brothers] both have brought here [i.e. as subject matter of the hearing] as rightful property’ (Wilhelm et al. 1932–2004: 2,472:10–14; No. 1201 A/B; Heiligkreuztal abbey, Biberach district, 1290)

- den Hof […] vnd di Mule / di er paidev […] hot

In a few cases, combined reference even to two men triggered neuter agreement, even though the referents’ grammatical properties as animate masculines are compatible. Of course, there are also cases where the formally expected masculine–feminine form actually does appear for mixed-gender groups, though this is a minority pattern in my data. All in all, the observed distribution of agreement markers makes one wonder in which morphosyntactic contexts, how often, and why these patterns occur, unexpected at first sight as they may be.

The phenomenon of languages using certain strategies to resolve a clash of grammatical features in mixed-gender groups is called—you guessed it—gender resolution. As the examples above show, MHG beide ‘both’ is notorious for displaying it in its declension form when its reference is to two distinct entities, especially when it refers to persons of incongruous (semantic) gender. This even goes for combined references containing morphologically ungendered personal pronouns like ich ‘I’ or du ‘you (SG)’, since they as well often implicitly encode information about the referenced person’s gender at the semantic level in context. For combinations of two inanimate nouns, there’s apparently a tendency for semantics to cause neuter across the board.

Moreover, referents of beide ‘both’ don’t need to be formally introduced into discourse by a coordination construction as we’ve seen in (5) and (6). For instance, in (7), the names Agnes and Lukas are syntactically part of different constituents.

- das vur Agnes mit h[er]n Lukas hant […] het gegeben ze coͧffenne ir hûz in kurdewenre gaſſen […] vn[de] hant bedi v[er]iehen […]

that Mrs. Agnes[F] with Mr. Lukas[M] hand […] has given to buying her house in Cordwainers’ Alley […] and have both-NOM.PL.N.ST testified

‘that Mrs. Agnes with Mr. Lukas’ authority […] put up her house in Cordwainers’ Alley for sale […] and [they] have both testified, […]’ (Wilhelm et al. 1932–2004: 5,156:11–16; No. N 202, Strasbourg, 1281)

How exactly both referents of beide are introduced into the grammatical context doesn’t matter so much because the quantifier very often modifies a pronoun like si ‘they (PL)’, which refers back to the pair collectively, or may itself act as a pronoun, like e.g. still in modern German Sie beide mögen Schokolade ‘Both of them like chocolate’ or Beide sind glücklich ‘Both are happy’.

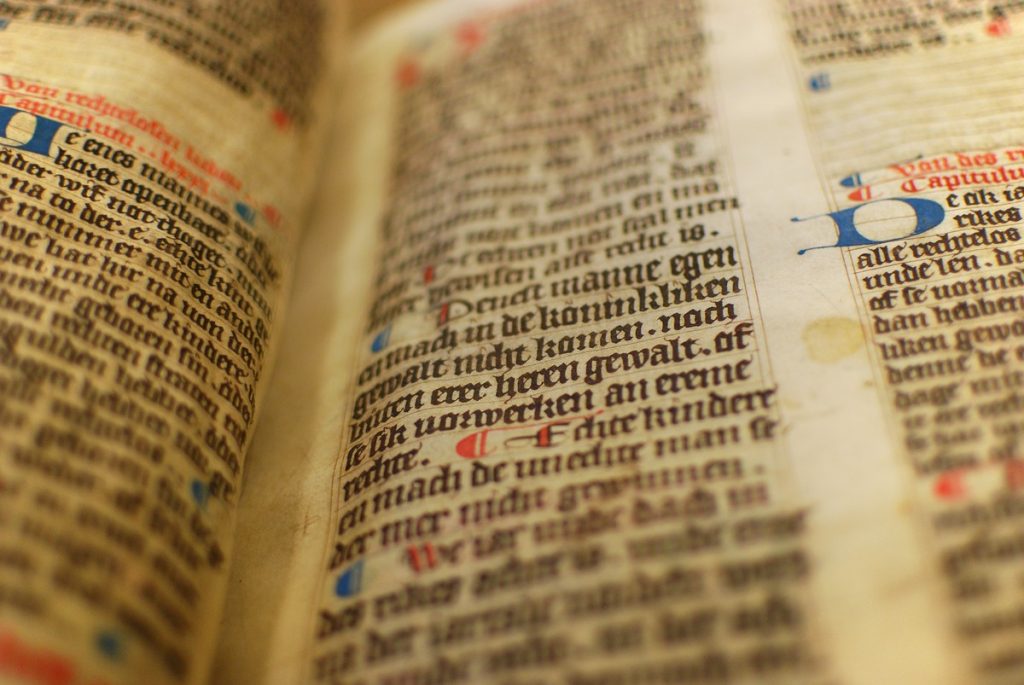

Language scholars have been aware of how the neuter serves as a resolution gender in the older stages of Germanic languages at large—not just in German, and it’s still attested for modern Icelandic and Faroese—at least since the 19th century. It’s also one of these things that, surprisingly, nobody’s yet had a thorough look at (i.e. morphosyntactically analyzed the crap out of) for MHG. That is, at least not regarding actual manuscripts especially of mundane, non-literary prose texts instead of only late 19th/early 20th century scholarly editions with regularized spelling and potentially even regularized grammar of the famous chivalric romances in verse. And this is the little knowledge gap that I mainly tried to address with my thesis.

Interestingly, you can apparently still find neuter with mixed-gender reference even in older contemporary German, although in individuating rather than aggregating contexts, since grammatical gender is only distinguished in the singular anymore. An example from the novel Stiller by the Swiss writer Max Frisch (1911–1991) that I happened to come across a while ago is given in (8a). Here, the neuter form jedes ‘each’ refers to Anatol Stiller and Sibylle, his affair.

- Stumm saßen sie auf der Erde, […] jedes mit einem Halm zwischen den sorgenvoll-verbissenen Lippen

mute sat 3PL.NOM on the ground […] each-NOM.PL.N.ST with a stem.of.grass between the sorrowful_sullen lips

‘Mutely they were sitting on the ground, […] each with a stem of grass between their sorrowfully sullen lips’ (Frisch 1954: 332–333)

While jedes looks like a typo from the point of view of modern Standard German since masculine jeder would be the expected resolution form for animates, it’s warranted historically, as evidenced by neuter æintwederez ‘either one’ in (9) relating to Ulrich and Margret. Also compare e.g. neuter unsereins ‘one like me’ (more literally, ‘one-of-ours’).

- der ſelbe vlrich / oder fraw Margret […] ſi leben peidev ſamte / oder ir æintwederez

the same Ulrich[M] or Mrs. Margret[F] […] 3PL.NOM live both-NOM.PL.N.ST altogether or 3PL.GEN either-NOM.SG.N.ST

‘the selfsame Ulrich or Mrs. Margret [… if] they are both living altogether or either one of them’ (Wilhelm et al. 1932–2004: 4,352:3–9; No. 3141 A/B, Brixen, 1298)

Reading suggestions

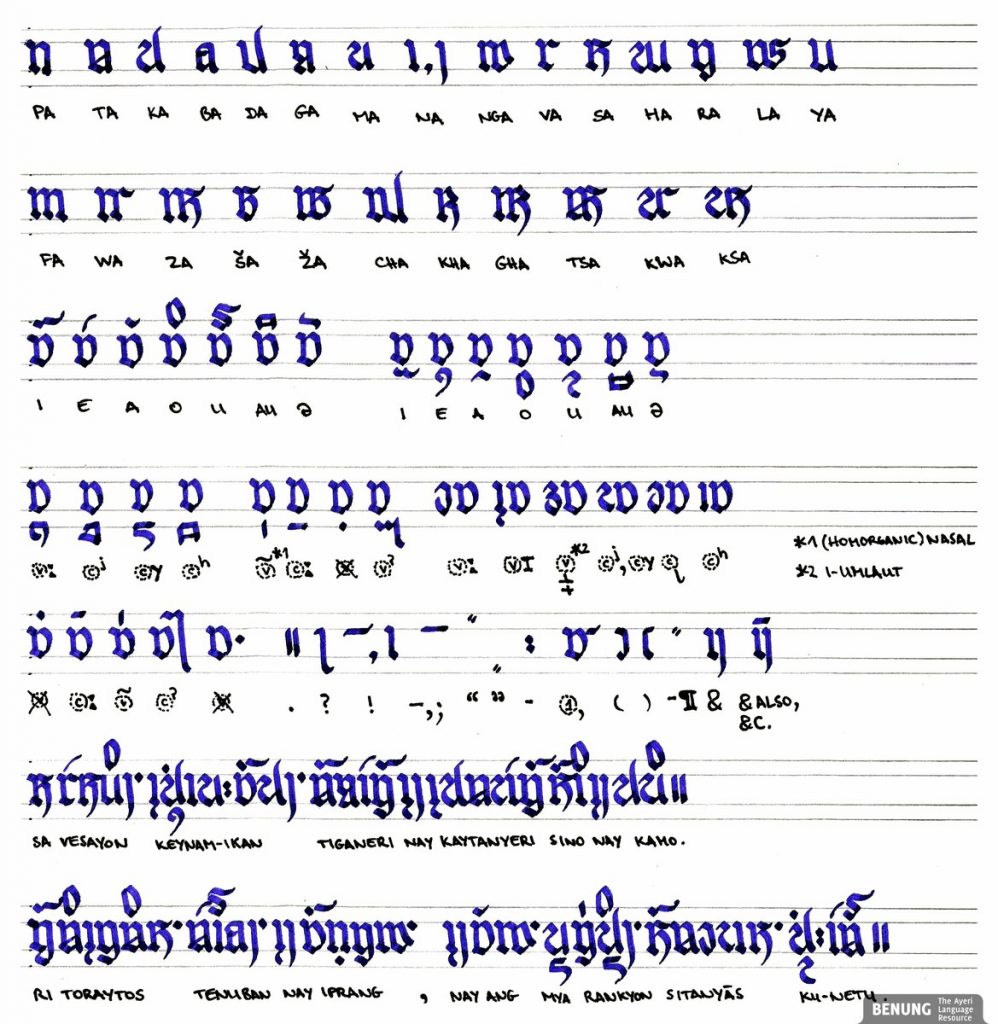

If these not quite so brief remarks piqued your interest—maybe also as a conlanger—and you want to look deeper into grammatical gender and associated resolution phenomena, the following three monographs might be starting points.

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2016. How gender shapes the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198723752.001.0001 (🔒). [Worldcat]

- Corbett, Greville. 1991. Gender (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781139166119 (🔒). [Worldcat]

- Wechsler, Stephen & Larisa Zlatić. 2003. The many faces of agreement (Stanford Monographs in Linguistics). Stanford: CSLI Publications. [Worldcat]

Aikhenvald and Corbett mostly approach the topic from the perspective of linguistic typology, Aikhenvald additionally has a sociolinguistic angle based on her fieldwork. Wechsler & Zlatić deal with the morphosyntactic side by example of Serbo-Croatian (i.e. Bosnian–Croatian–Montenegrin–Serbian). This last book is probably the least geared toward casual readers of the three, but chapter 8 is concerned with modeling gender resolution in terms of a theory-driven explanation of empirical data that may be worth a look and also informed my own research.

With a special focus on how grammatical gender manifests in German, as well as the semantic, social, cultural, and political complexities involved, these three references might also make interesting reading (in German):

- Klein, Andreas. 2022. Wohin mit Epikoina? Überlegungen zur Grammatik und Pragmatik geschlechtsindefiniter Personenbezeichnungen. In Gabriele Diewald & Damaris Nübling (eds.), Genus – Sexus – Gender (Linguistik – Impulse & Tendenzen 95), 135–189. Berlin: De Gruyter. DOI: 10.1515/9783110746396-005 (🔓). [Worldcat]

- Köpcke, Klaus-Michael & David A. Zubin. 2017. Genusvariation: Was offenbart sie über die innere Dynamik des Systems? In Marek Konopka & Angelika Wöllstein (eds.), Grammatische Variation: Empirische Zugänge und theoretische Modellierung (Institut für Deutsche Sprache Jahrbuch 2016), 203–228. Berlin: De Gruyter. DOI: 10.1515/9783110518214-013 (🔒). [Worldcat]

- Kotthoff, Helga & Damaris Nübling. 2018. Genderlinguistik: Eine Einführung in Sprache, Gespräch und Geschlecht (Narr Studienbücher). Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto. [Worldcat]

Köpcke and Zubin have also published on German gender in English, for instance, Zubin & Köpcke (2009) (🔒) and Köpcke, Panther & Zubin (2010) (🔒).

Besides gender resolution, number resolution is of course also a thing, and I’ve been wondering if any languages, natural or invented, have formalized politeness resolution. German hasn’t despite the prominent T–V distinction, so mixing informal/intimate du and formal/distant Sie in address always leads to awkward phrasing.

tl;dr

In texts from the Upper German dialect group of Middle High German (c. 1050–1350 CE), neuter plural forms instead of masculine–feminine ones can often be found in agreement forms referencing mixed-gender groups of men and women collectively. This is striking because it seems unmotivated on purely morphological grounds. Neuter agreement forms can also be found more generally in combined reference to things regardless of their individual grammatical gender. I surveyed faithful transcriptions of medieval manuscripts from two source collections with regard to the detailed grammatical contexts involved in triggering neuter gender agreement in combined reference by example of beide ‘both’. My aim was to gain a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon than what the main reference works on Middle High German and a previous study from the 1970s provide.

References

- de Boor, Helmut & Roswitha Wisniewski (Hrsg.). 1988. Das Nibelungenlied. After Karl Bartsch’s edition. 22nd edn. (Deutsche Klassiker des Mittelalters). Mannheim: Brockhaus.

- Braune, Wilhelm & Frank Heidermanns. 2023. Althochdeutsche Grammatik. Vol. 1: Phonologie und Morphologie. 17th edn. (Sammlung kurzer Grammatiken germanischer Dialekte, A. Hauptreihe 5). Berlin: De Gruyter. DOI: 10.1515/9783111210537 (🔒). [Worldcat]

- Frisch, Max. 1954. Stiller. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. [Worldcat]

- Heidelberg, University Library, Cod. Pal. germ. 848. [Heidelberg Univ. Lib.; HSC]

- Klein, Thomas, Hans-Joachim Solms, & Klaus-Peter Wegera. 2009. Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Vol. 3: Wortbildung. Tübingen: Niemeyer. DOI: 10.1515/9783110971835 (🔒). [Worldcat]

- Klein, Thomas, Hans-Joachim Solms & Klaus-Peter Wegera. 2018. Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. Vol. 2: Flexionsmorphologie. Berlin: De Gruyter. DOI: 10.1515/9783110523522 (🔒). [Worldcat 1, 2]

- Paul, Hermann, Thomas Klein, Hans-Joachim Solms, Klaus-Peter Wegera, Ingeborg Schröbler & Hans-Peter Prell. 2007. Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik. 25th edn. Tübingen: Niemeyer. DOI: 10.1515/9783110942354 (🔒). [Worldcat]

- Schmid, Hans U. 2023. Althochdeutsche Grammatik. Vol. 2: Grundzüge einer deskriptiven Syntax. 2nd edn. (Sammlung kurzer Grammatiken germanischer Dialekte, A. Hauptreihe 5). Berlin: De Gruyter. DOI: 10.1515/9783110782493 (🔒). [Worldcat]

- Wilhelm, Friedrich, Richard Newald, Helmut de Boor, Diether Haacke & Bettina Kirschstein (eds.). 1932–2004. Corpus der altdeutschen Originalurkunden bis zum Jahr 1300. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. http://tcdh01.uni-trier.de/cgi-bin/iCorpus/CorpusIndex.tcl (2023-09-23). [Worldcat]