In this series of blog articles—taken (more or less) straight from the current working draft of chapter 5.4 of the new grammar for better visibility and as a direct update of an old article (“Flicking Switches: Ayeri and the Austronesian Alignment”, 2012-06-27)—I will finally reconsider the way verbs operate with regards to syntactic alignment.

All articles in this series: Typological Considerations · ‘Trigger Languages’ · Definition of Terms · Some General Observations · Verb agreement · Syntactic Pivot · Quantifier Float · Relativization · Control of Secondary Predicates · Raising · Control · Conclusion

Now that a few tests have been conducted, let us collect the results. As Table 1 shows, Tagalog and Ayeri are not really similar in syntax despite superficial similarities in morphology. According to Kroeger (1991)’s thesis—which essentially seeks to critically review and update Schachter (1976)’s survey by leaning on LFG theory—Tagalog prefers what Kroeger analyzes as the nominative argument for most of the traits usually associated with subjects listed below. That is, in his analysis, the nominative argument is the NP in a clause which is marked on the verb, which corresponds to Schachter (1976)’s ‘topic’, or Schachter (2015)’s ‘trigger’—’trigger’ is also the term often seen in descriptions of constructed languages in this respect. Kroeger (1991) finds in his survey that the nominative argument is largely independent from the actor, so that the logical subject is not necessarily the syntactic subject; what Schachter (1976) calls ‘topic’ also does not behave like a pragmatic topic in terms of statistics.

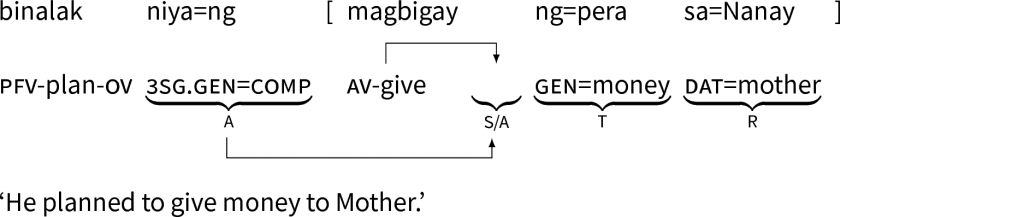

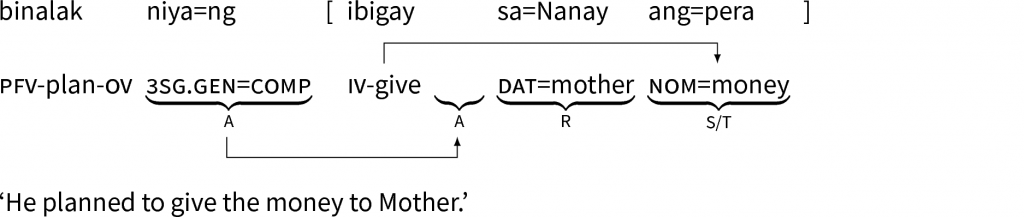

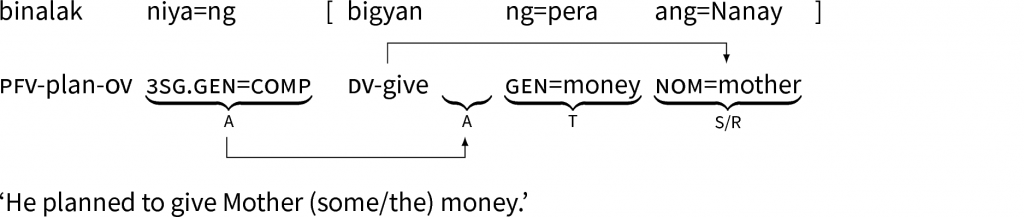

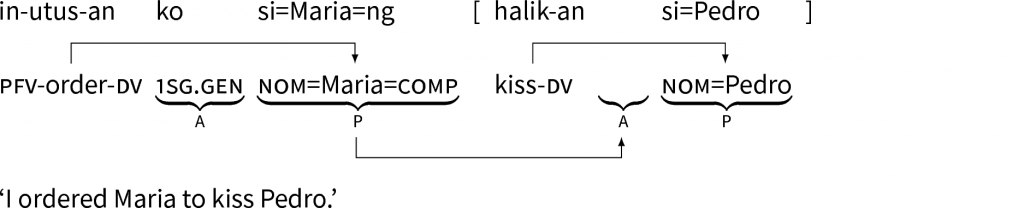

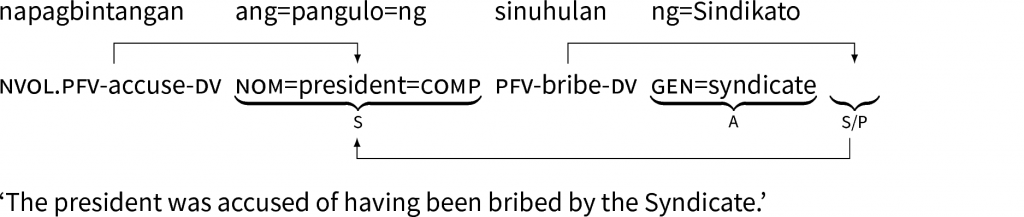

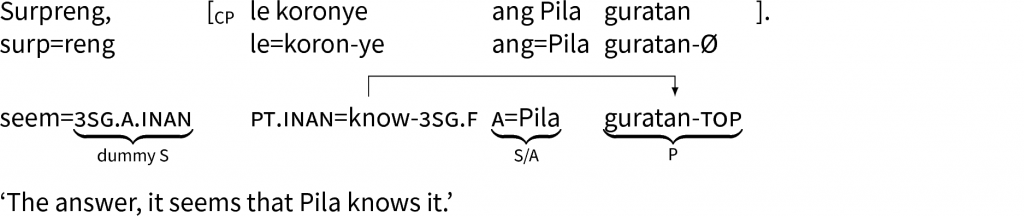

Essentially, what Tagalog does according to Kroeger (1991)’s analysis, is to generalize voice marking beyond passive voice, so that any argument of the verb can be the subject. However, unlike passives in English, higher-ranking roles (for passives, the agent) appear not to be suppressed or to be demoted to adverbials like it happens in English with the periphrasis of the agent with by in passive clauses. Linguists have been grappling for a long time with this observation, and constraint-based approaches, such as LFG (recently, Bresnan et al. 2016) or HPSG (Pollard and Sag 1994) pursue, may be able to explain things more succinctly than structuralist ones due to greater flexibility. In any case, Kroeger (1991) avoids the terms ‘active’ or ‘passive’ possibly for this reason, and instead uses ‘actor voice’ (AV), ‘objective voice’ (OV), ‘dative/locative voice’ (DV) etc. (14–15).

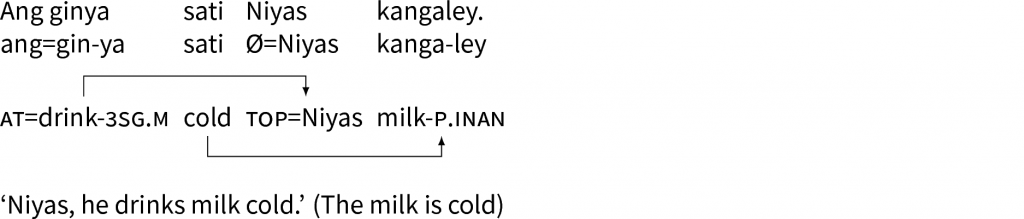

Ayeri, in contrast to Tagalog, very much prefers the actor argument (called agent here for consistency) for traits usually associated with subjects, independent of whether the agent is also the topic of the clause—in Ayeri it is the topic which is marked on the verb, not the nominative argument. In spite of a few irregularities like patient agreement in agentless clauses and using topicalization as a way to disambiguate the syntactic pivot in ambiguous cases, Ayeri is remarkably consistent with a NOM–ACC language. The fact that there is a subject in the classic, structural sense is also evidence for the hypothesis that Ayeri is configurational. Since it clearly prefers agent NPs over other NPs, not all arguments of a verb are on equal footing. Tagalog, on the other hand, treats the arguments of verbs in a much more equal manner.

| Criterion | Tagalog | Ayeri |

|---|---|---|

| Marked on the verb | nominative argument (NOM) | topic argument (TOP) |

| Verb agreement | optional; if present with NOM, independent of being A | required; typically with A, independent of being TOP |

| Syntactic pivot | determined by NOM, independent of being A | usually with A, but determined by TOP in ambiguous cases |

| Quantifier float | referring to NOM, independent of being A | referring to A, independent of being TOP |

| Relativization | only of NOM, independent of being A | (all NPs may be relativized) |

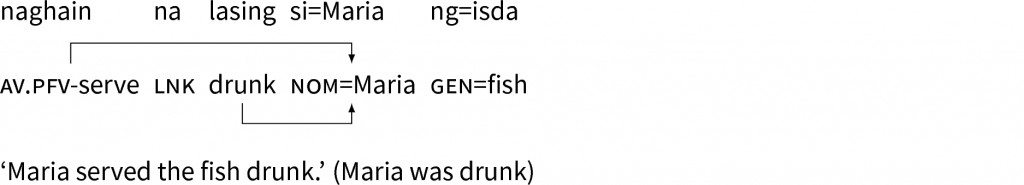

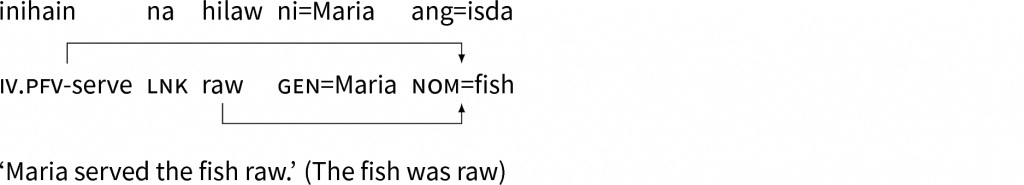

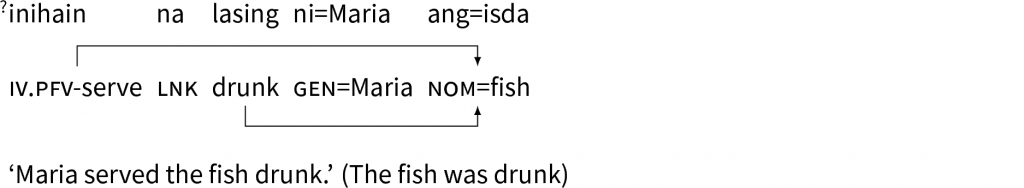

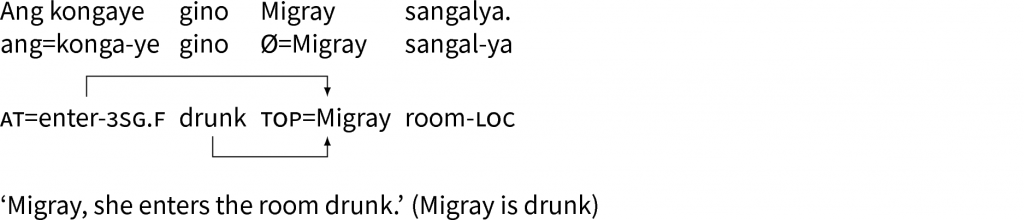

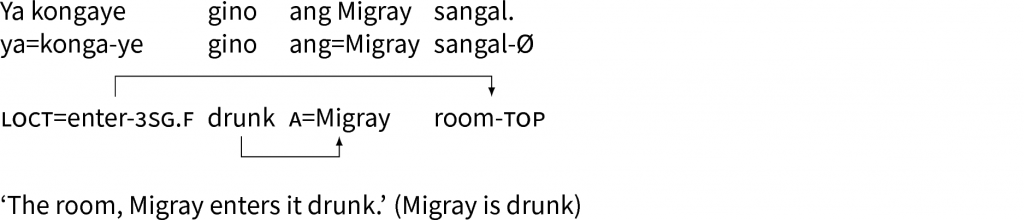

| Control of secondary predicates | referring to NOM, independent of being A | referring to A or P depending on semantics, but independent of being TOP |

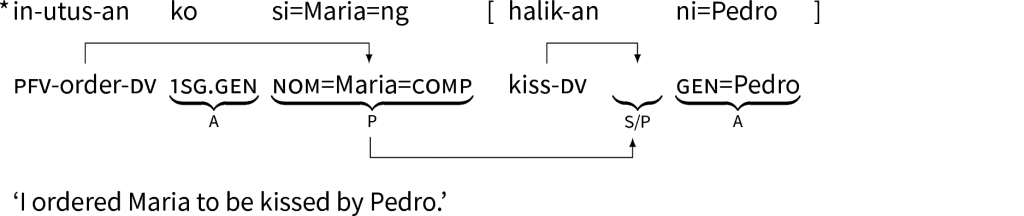

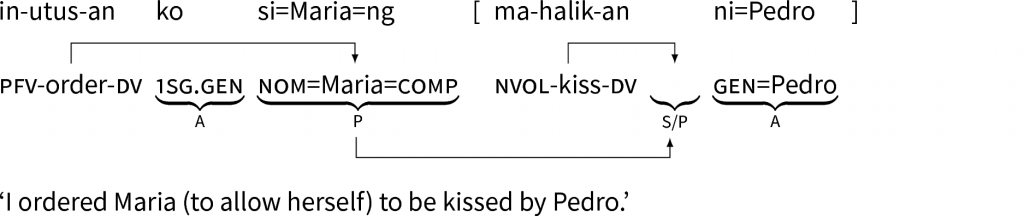

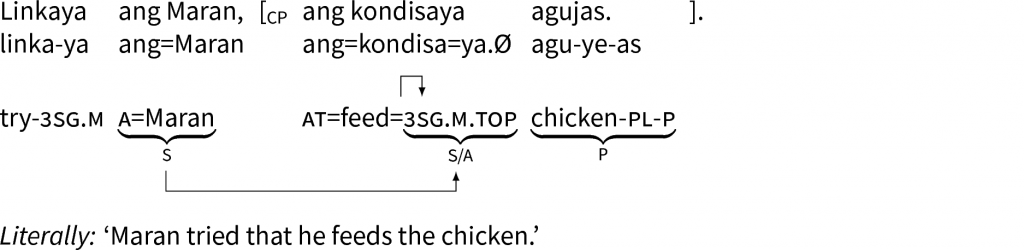

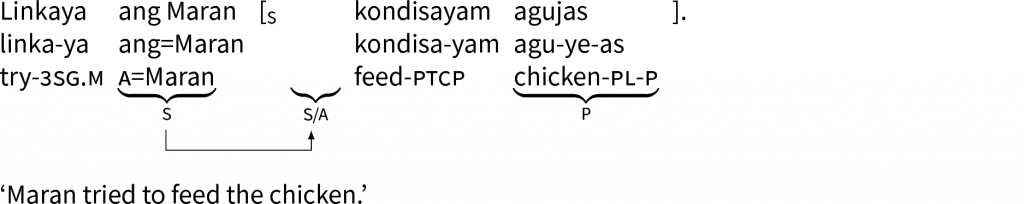

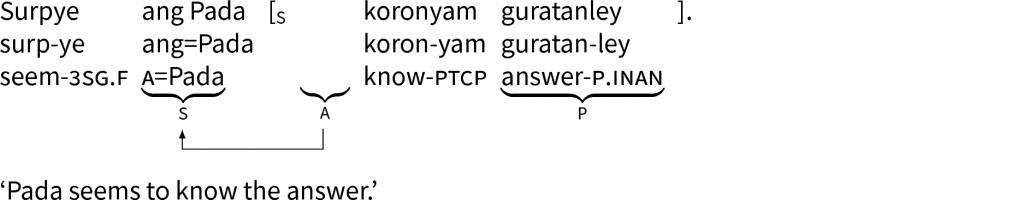

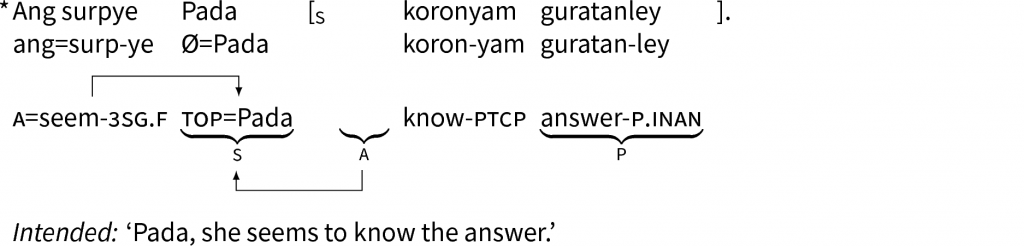

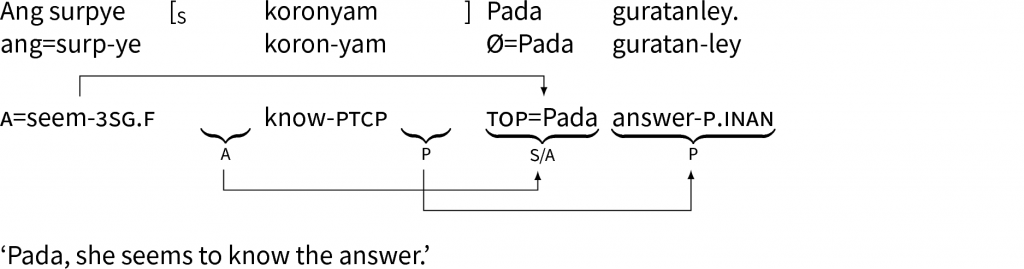

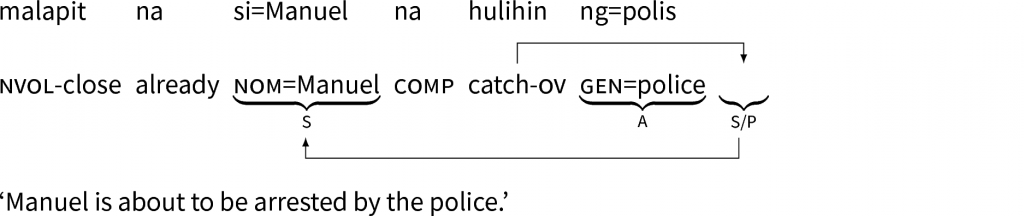

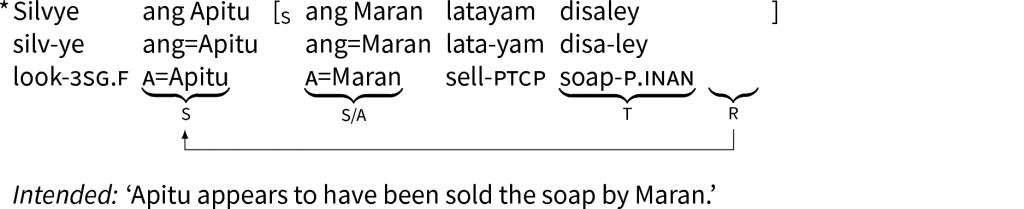

| Raising | usually of NOM; A possible but marked for some | only of A, independent of being TOP; no ECM |

| Control | A deletion target, independent of being NOM (with exceptions) | A deletion target, independent of being TOP |

It was pointed out before that in Tagalog, the syntactic pivot depends on what is marked as a subject (Kroeger 1991: 30–31). This and other examples from Kroeger (1991) may make it seem like Tagalog is not fixed with regards to the distinction between NOM–ACC and ERG–ABS alignment. However, Kroeger (1991) also points out that there is a statistically significant preference to select patient arguments as subjects, and that OV forms of verbs are “morphologically more ‘basic’” (53) than their respective AV counterparts. These observations point towards an interpretation of Tagalog as syntactically ergative, though Kroeger (1991) deems such an interpretation problematic due to non-nominative agents keeping their status as arguments of the verb—which also distinguishes Tagalog from an ergative languages like Dyirbal, where “ergative (or instrumental) marked agents are relatively inert, playing almost no role in the syntax, and have been analyzed as oblique arguments” (54).

In conclusion, is Ayeri a so-called ‘trigger language’? Yes and no. It seems to me that what conlangers call ‘trigger language’ mostly refers to just the distinct morphological characteristic of languages like Tagalog by which a certain NP is marked on the verb with a vague notion that this NP is in some way important in terms of information structure.[1. I want to encourage everyone to actually do some reading of the professional literature on a given topic instead of only relying on the second-hand knowledge of other people in the conlanging community. It’s hard but you’ll learn from it. With the internet, finding articles and books is as easy as ever. This is one of the reasons why I give citations under the more serious blog articles, and make sure to link literature that is legally available online.] Ayeri incorporates this morphological feature and may thus be counted among ‘trigger languages’ by this very broad definition. However, the real-world Austronesian alignment as a syntactic phenomenon goes much deeper than that and is much more intriguing, as I have tried to show in this series of blog articles, and I did not even cover all of the effects Kroeger (1991) describes in his survey. Ayeri, in syntactically behaving rather consistently like a NOM–ACC language, (somewhat sadly, in retrospect) misses the point completely if ‘trigger language’ is understood to also entail syntactic characteristics of Philippine languages.

- Bresnan, Joan et al. Lexical-Functional Syntax. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2016. Print. Blackwell Textbooks in Linguistics 16.

- Kroeger, Paul R. Phrase Structure and Grammatical Relations in Tagalog. Diss. Stanford University, 1991. Web. 17 Dec. 2016. ‹http://www.gial.edu/wp-content/uploads/paul_kroeger/PK-thesis-revised-all-chapters-readonly.pdf›.

- Pollard, Carl and Ivan A. Sag. Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar. Chicago, IL: U of Chicago P, 1994. Print. Studies in Contemporary Linguistics.

- Schachter, Paul. “The Subject in Philippine Languages: Topic, Actor, Actor-Topic, or None of the Above?” Subject and Topic. Ed. Charles N. Li. New York: Academic P, 1976. 493–518. Print.

- ———. “Tagalog.” Syntax—Theory and Analysis: An International Handbook. Ed. Tibor Kiss and Artemis Alexiadou. Vol. 3. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2015. 1658–1676. Print. Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science 42. DOI: 10.1515/9783110363685-007.