In this series of blog articles—taken (more or less) straight from the current working draft of chapter 5.4 of the new grammar for better visibility and as a direct update of an old article (“Flicking Switches: Ayeri and the Austronesian Alignment”, 2012-06-27)—I will finally reconsider the way verbs operate with regards to syntactic alignment.

All articles in this series: Typological Considerations · ‘Trigger Languages’ · Definition of Terms · Some General Observations · Verb agreement · Syntactic Pivot · Quantifier Float · Relativization · Control of Secondary Predicates · Raising · Control · Conclusion

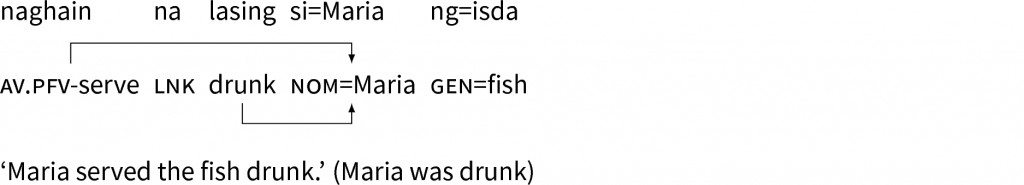

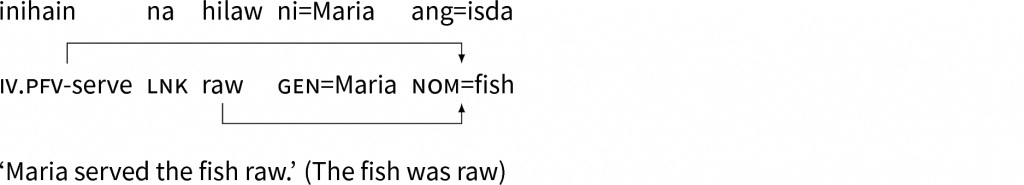

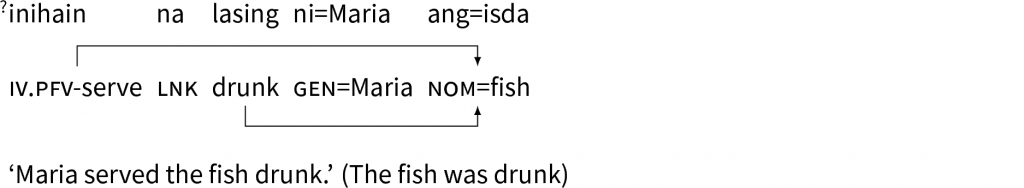

Secondary predicates in Tagalog are interesting insofar as depictive adjectives which occur after the verb always modify the nominative argument:

Kroeger (1991: 30) explains that (1c) is anomalous, since the subject is indicated as ang isda ‘the fish’, however, lasing ‘drunk’ is not a property usually associated with fish—it would fit better with ‘Maria’. However, this interpretation would be ungrammatical since ‘Maria’ is not the subject of the clause.

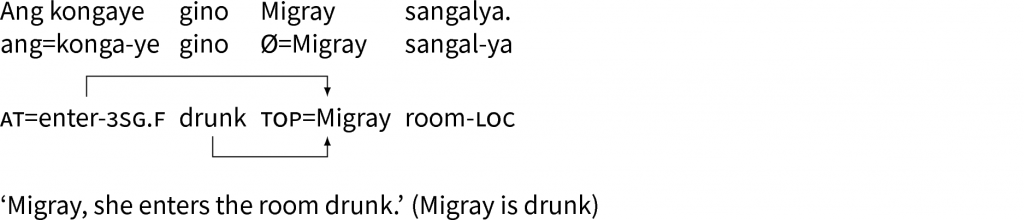

Secondary predicates in Ayeri also follow the finite verb, and they refer to the agent. If what was identified as the topic would be the subject like in Tagalog, thus, the reference of the adjective should change in the way shown in (1). However, as we will see below, this is not the case.

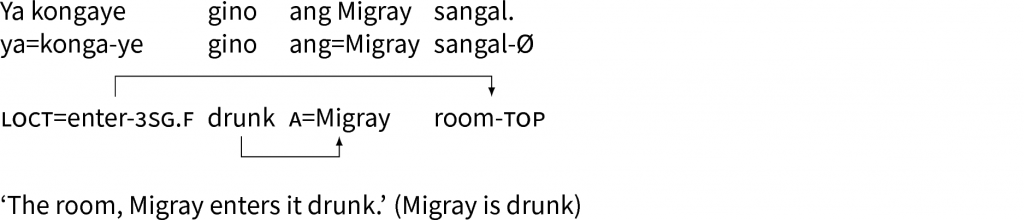

In (2a), the topic NP, Migray, happens to be the same NP that is modified by the secondary predicate, gino ‘drunk’: Migray is drunk. However, (2b) generates the same reading even though this time, sangal ‘the room’ is marked as the topic of the clause. A reading in which the room is drunk cannot be forced by morphological means, although it needs to be pointed out that predicative adjectives relating to the object inhabit the same postverbal position. Considering structure alone, the sentence in (2b) is ambiguous, though context certainly favors the reading provided in the translation of (2b), since ‘drunk’ is not typically a property of rooms.

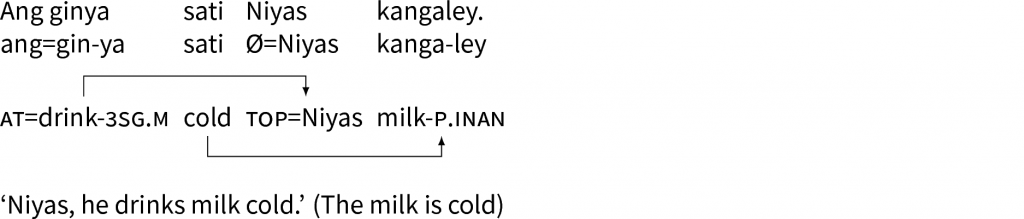

Different than in (2), the adjective in (3), sati ‘cold’, refers to the object of the clause, kangaley ‘milk’, even though kangaley is not the topic of the clause. By structure alone, Niyas could also be the one who is cold, rather than the milk, however, this would be unlikely considering context and extralinguistic experience. Equally unlikely is the possible interpretation of the milk becoming cold by Niyas’ drinking it.

Different than in Tagalog, thus, it is not morphology but the meaning of the verb which determines whether the postverbal predicative adjective refers to the agent or the patient.[1. Unfortunately, Kroeger (1991) does not provide any examples of object predicatives in Tagalog, and neither does Schachter and Otanes (1972) readily contain information on these.] However, since in Ayeri, the predicative adjective following the verb can refer to either the agent or the patient depending on context, this test does not have a very clear outcome. At least we could establish here that alternations in the morphological marking of the privileged NP—tentatively, the topic—has no impact on the relation between adjective and noun. The marking on the verb is thus not used for manipulating grammatical relations in this context, unlike in Tagalog.

- Kroeger, Paul R. Phrase Structure and Grammatical Relations in Tagalog. Diss. Stanford University, 1991. Web. 17 Dec. 2016. ‹http://www.gial.edu/wp-content/uploads/paul_kroeger/PK-thesis-revised-all-chapters-readonly.pdf›.

- Schachter, Paul and Fe T. Otanes. 1972. Tagalog Reference Grammar. Berkeley: U of California P, 1983. Google Books. Google, 2011. Web. 6 Nov. 2011. ‹http://books.google.com/books?id=E8tApLUNy94C›.