In this series of blog articles—taken (more or less) straight from the current working draft of chapter 5.4 of the new grammar for better visibility and as a direct update of an old article (“Flicking Switches: Ayeri and the Austronesian Alignment”, 2012-06-27)—I will finally reconsider the way verbs operate with regards to syntactic alignment.

All articles in this series: Typological Considerations · ‘Trigger Languages’ · Definition of Terms · Some General Observations · Verb agreement · Syntactic Pivot · Quantifier Float · Relativization · Control of Secondary Predicates · Raising · Control · Conclusion

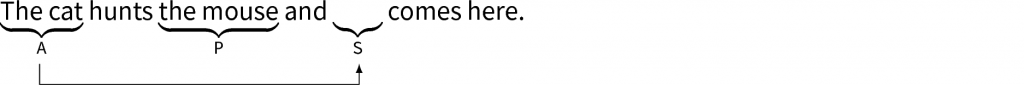

Since we have just dealt with aspects of syntactic alignment in the last installment and found that Ayeri behaves a little oddly with regards to this, it may be interesting to perform another test on declarative statements and their syntactic pivot as well. A simple test which Comrie (1989: 111–114) describes in this regard is to test coreference in coordinated clauses. In coordinated clauses, it seems to be not uncommon for the subject of the second conjunct to drop out. Thus, in English, which behaves very much in terms of NOM–ACC alignment in this regard, we get the following result:

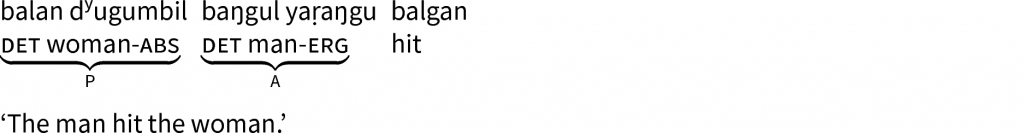

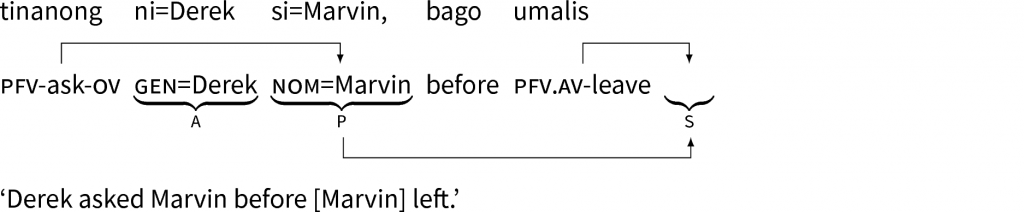

In the English example in (1), the cat constitutes the coreferential subject in (1d). This NP is the intransitive subject S of (1b) and the agent A of (1a). English thus typically has NOM–ACC alignment, since it treats S and A alike. In an ERG–ABS language, then, we would expect the opposite case: S and P should be treated alike. In Dyirbal, we find the situation depicted by the examples in (2).

In (2), we find that balan dʸugumbil ‘the woman’ is coreferential in (2d). This is the S of (2c), and the P of (2a). Dyirbal, thus, treats S and P alike, as predicted for an ERG–ABS language—at least in this case, since Comrie (1989: 113) also explains that 1SG and 2SG pronouns in Dyirbal behave in terms of NOM–ACC. Comrie (1989) also notes that some languages do not show a clear preference for whether the A or P of the transitive clause in the first conjunct is the preferred reference of the S of the intransitive clause in the second conjunct.

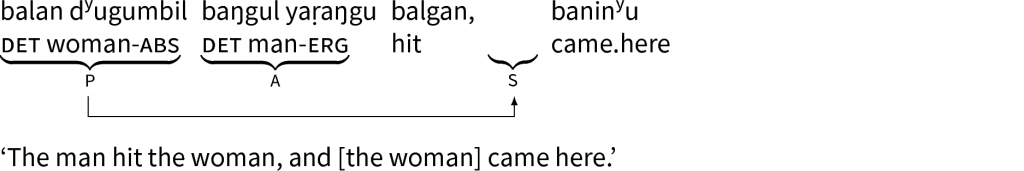

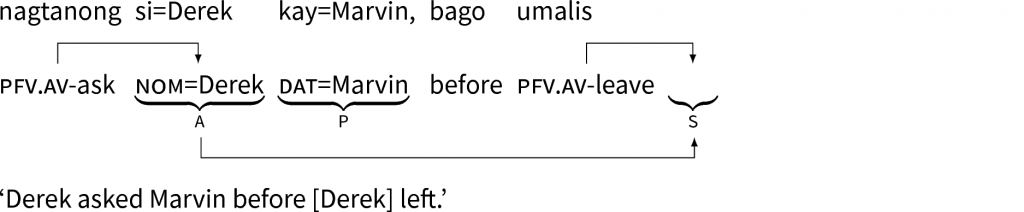

For Tagalog, as Kroeger (1991) explains, “the deletion is not obligatory but null nominative arguments are always interpreted as referring to the nominative argument of the main clause” (30). Due to the way Tagalog treats subjects, however, the nominative argument can be formed by either NP in (3) with the voice marked accordingly on the verb.[1. Thus, compare the English passive sentence Marvini was asked by Derekj before hei left with (3a). In English, the reference of he is ambiguous between the syntactic subject Marvin and the agent Derek, however. As we have seen above, though, Tagalog would also be able to make a subject of an oblique argument, not just of the patient/theme or the recipient. The actor of the Tagalog sentence is also basically an object, not demoted to an adverbial as in English (Kroeger 1991: 38–44).]

What can be observed in Tagalog is that in (3a), the dropped S argument in the second conjunct, bago umalis … ‘before … leaves’, is coreferential with Marvin, since he is marked as the subject of the first conjunct. Since Marvin is the theme (above marked P for ‘patient’ more generally) of tanong ‘ask’, the clause needs to be marked for objective voice. On the other hand, in (3b), it is Derek who is the subject of the clause, so it is also he who leaves; the verb in the first conjunct clause is marked for actor voice according to the asker as the actor (A) being the subject.

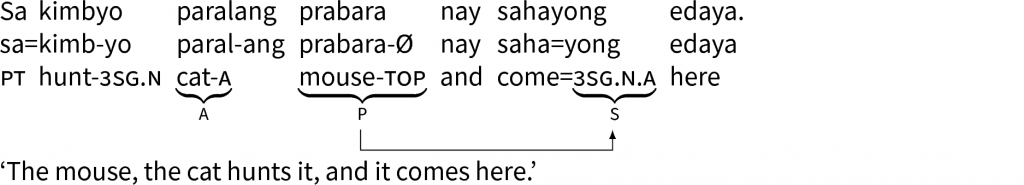

In order to now investigate what the situation is in Ayeri, let us return to our initial set of examples. These examples feature two animals which are treated both as animate neuters. Anaphoric reference is thus potentially ambiguous between paral ‘cat’ and prabara ‘mouse’.

While it is possible in Ayeri to not repeat the coreferential NP in a conjunct clause verbatim, Ayeri still appears to avoid an empty subject slot. Thus, the verb sahayong ‘it comes’ in (4b) displays a pronominal clitic, -yong ‘it’, which constitutes the resumptive subject pronoun of the clause. In (4d) at least, this pronoun is coreferential with the subject in the first conjunct, paral ‘cat’. Seeing as Tagalog switches the subject around by altering the voice marking on the verb, it is certainly illustrative to check how Ayeri fares if the topic is swapped to prabara ‘mouse’.

In (5), the resumptive pronoun is indicated to not refer to the first conjunct’s agent/subject, paral, but to its theme/object, prabara. This may be explained by topicalization: the sentence is about the mouse, so the underspecified argument in the second conjunct, in absence of topic marking that would indicate otherwise, corresponds to the topic. Interestingly, the result is structurally similar to the example of Tagalog in (3) above. It is too early yet, however, to conclude that what was called ‘topic’ so far is the subject; Ayeri is merely not completely unambiguous in this context. Since Tagalog allows any NP of a clause to be the subject, as illustrated by (1) of installment 4 in this series, let us test whether the behavior just described for Ayeri also holds in other contexts of topicalization. The following example presents sentences of differently case-marked topic NPs each, but in every case, the agent NP and the topicalized NP consist of a human referent. Both referents share the same person features so that the verb in the coordinated intransitive clause can theoretically license either of them as its antecedent.

-

-

{Yam ilya} {ang Akan} ilonley Maran nay sarayāng.

yam=il-ya ang=Akan ilon-ley Ø=Maran nay sara=yāng

DATT=give-3SG.M A=Akan present-P.INAN TOP=Maran and leave=3SG.M.A

‘Maran, Akan gives him a present, and he leaves.’ (Maran leaves)

-

{Na pahya} {ang Maran} ilonley Diyan nay sarayāng.

na=pah-ya ang=Maran ilon-ley Ø=Diyan nay sara=yāng

GENT=take.away-3SG.M A=Maran present-P.INAN TOP=Diyan and leave=3SG.M.A

‘Diyan, Maran takes the present away from him, and he leaves.’ (Diyan leaves)

-

{Ya bahaya} {ang Diyan} Maran nay sarayāng.

ya=baha-ya ang=Diyan Ø=Maran nay sara=yāng

LOCT=baha-3SG.M A=Diyan TOP=Maran and leave=3SG.M.A

‘Maran, Diyan shouts at him, and he leaves.’ (Maran leaves)

-

{Ri su-sunca} {ang Diyan} ilonley Sedan nay sarayāng.

ri=su~sunt-ya ang=Diyan ilon-ley Ø=Sedan nay sara=yāng.

INST=ITER~claim-3SG.M A=Diyan present-P.INAN TOP=Sedan and leave=3SG.M.A

‘Sedan, Diyan reclaims the present with his help, and he leaves.’ (Sedan leaves)

-

{Sā pinyaya} {ang Maran} tatamanyam Sedan nay sarayāng.

sā=pinya-ya ang=Maran tataman-yam Ø=Sedan nay sara=yāng

CAUT=ask-3SG.M A=Maran forgiveness-DAT TOP=Sedan and leave=3SG.M.A

‘Sedan, he makes Maran ask for forgiveness, and he leaves.’ (Sedan leaves)

-

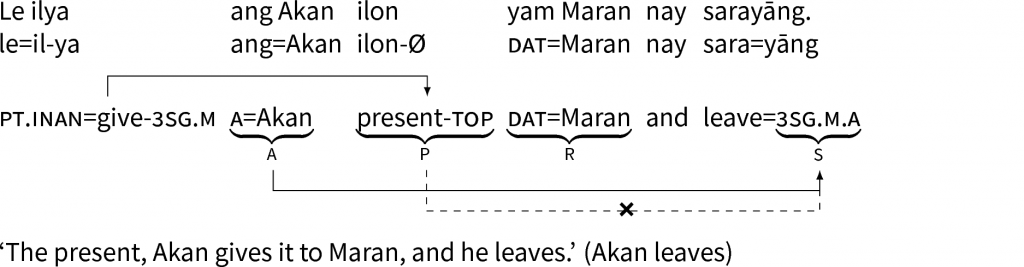

In each of the sentences in (6), it is the topicalized NP which is identified as the antecedent for sarayāng ‘he leaves’. Does this mean Ayeri does, in fact, use Austronesian alignment? While the above examples certainly suggest it, let us not forget that the verb in the coordinated clause could theoretically pick either the agent NP or the topicalized NP as its controller. Things look slightly different, however, if the reference of the verb is unambiguous, for instance, because the topicalized argument cannot logically be the agent of the coordinated clause:

In (7), the first conjunct’s verb, as the head of its clause, specifies that the topic of the clause is the patient (P), which is embodied by ilon ‘present’. This NP, however, is not a very typical agent for the verb in the second conjunct, sara- ‘leave’. Besides, this verb is conjugated so as to require an animate masculine controller, whereas ilon is inanimate, as shown by the topic marker le. Ilon is thus not a suitable controller for sarayāng, since their person-feature values clash with each other—the ANIM and GEND values in particular:

-

-

ilon N (↑ PRED) = ‘present’ (↑ INDEX) = ↓ (↓ PERS) = 3 (↓ NUM) = SG (↓ ANIM) = – (↓ GEND) = INAN -

sarayāng I (↑ PRED) = ‘leave ‹(↑ SUBJ)›’ (↑ SUBJ) = ↓ (↓ PRED) = ‘pro’ (↓ PERS) = 3 (↓ NUM) = SG (↓ ANIM) = + (↓ GEND) = M (↓ CASE) = A

-

As before, there are two masculine NPs in the first conjunct which form suitable antecedents on behalf of being animate masculine as required: the agent (A) Akan and the recipient (R) Maran. Of the remaining non-topic NPs, Ayeri considers the agent to rank higher as a secondary topic on the thematic hierarchy than the recipient. The agent hence forms the preferred controller for sarayāng.

- Thematic hierarchy (Bresnan et al. 2016: 329):agent > beneficiary > experiencer/goal > instrument > patient/theme > locative

In cases where the topic in the first conjunct can safely be ruled out as the controller of the pronominal in the second conjunct, the syntactic pivot, thus, defaults to the highest-ranking semantically coherent NP. In most cases, Ayeri will therefore group the intransitive subject and the transitive agent together. For most verbs, this is also reflected by case marking, as we have seen above in (4): the S of an intransitive clause receives the same case marker as the A of a transitive clause: -ang/ang for animate referents, and reng/eng for inanimate referents. The case described initially, where the topic marking basically determines the controller of the coordinated intransitive clause, which is reminiscent of Tagalog’s syntax, is essentially a strategy to disambiguate between two possible controllers for the same target.

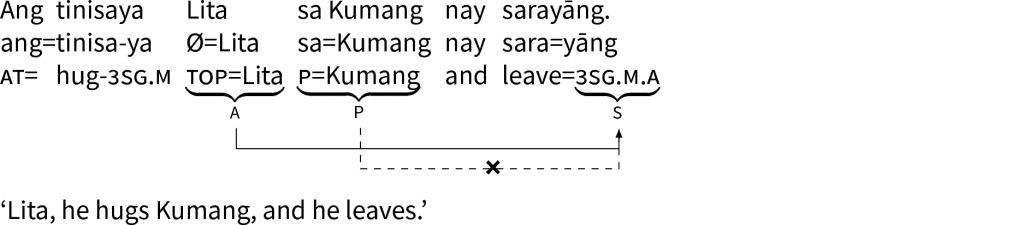

When only one of the referents in the transitive conjunct is eligible as the controller of the subject of the intransitive conjunct at the same time, A and P are regularly indicated by person agreement, since Ayeri requires a resumptive pronominal clitic in the intransitive clause, as indicated above. The affix on the verb thus has the status of a pronominal predicator, compare (10).

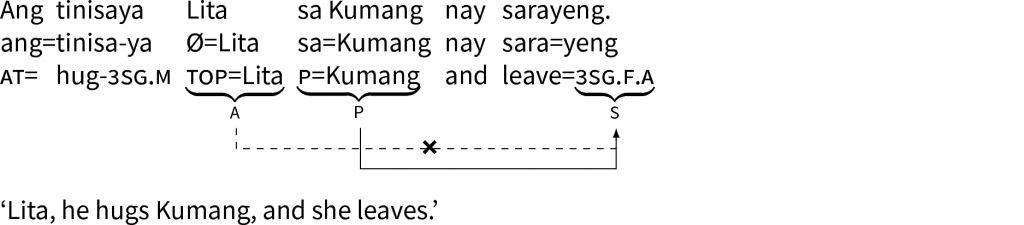

In (10a), the verb in the second conjunct, sarayāng ‘he leaves’ is marked for a masculine third-person subject. The only available controller in the first conjunct is Lita on behalf of being male, since Kumang is female. Hence, in (10b) the verb of the intransitive conjunct, sarayeng ‘she leaves’, finds its controller only in Kumang.

- Bresnan, Joan et al. Lexical-Functional Syntax. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2016. Print. Blackwell Textbooks in Linguistics 16.

- Comrie, Bernard. Language Universals and Linguistic Typology. Syntax and Morphology. 2nd ed. London: Blackwell, 1989. Print.

- Kroeger, Paul R. Phrase Structure and Grammatical Relations in Tagalog. Diss. Stanford University, 1991. Web. 17 Dec. 2016. ‹http://www.gial.edu/wp-content/uploads/paul_kroeger/PK-thesis-revised-all-chapters-readonly.pdf›.

- Ramos, Teresita V. and Resty M. Cena. Modern Tagalog: Grammatical Explanations and Exercises for Non-native Speakers. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1990. Print.