With my dissertation off the table, I guess I needed something new to delve into. As I mentioned in a previous blog post, during the summer, Toki Pona has struck my fancy. After about three months of casual practice, it looks like I can produce mostly grammatical sentences. I’m also growing in my ability to understand others’ written sentences, which can be challenging, because, within the domain of content words, there are no hard part-of-speech boundaries. Think “the old man the boat” or “the horse raced past the barn fell,” except as a general feature of the language, though with arguably better ways to tell subject and object apart than in English.

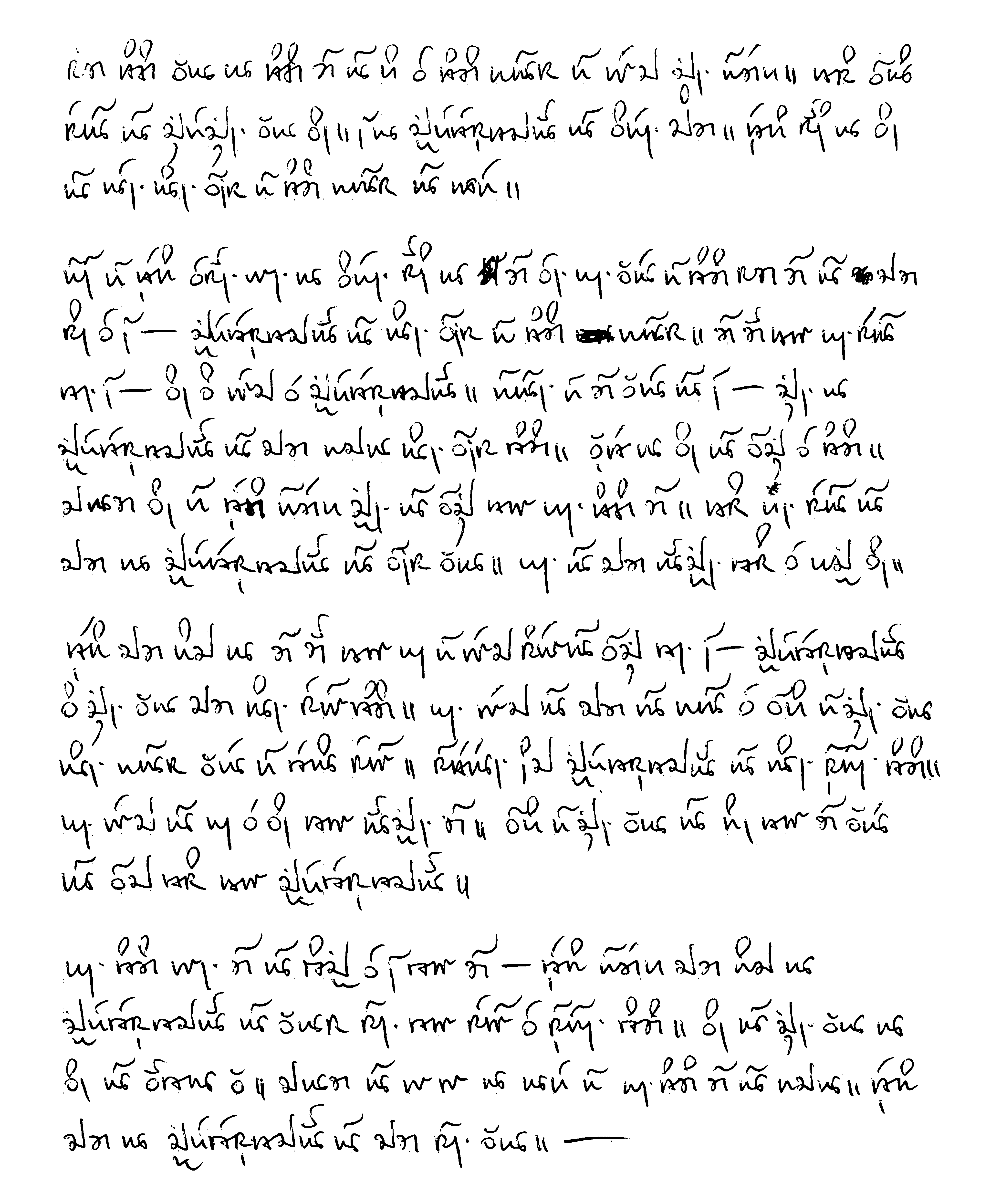

I’ve recently come up with the following small text that I’ve slightly edited before writing it down as below. Apart from that, I’ve also recently experimented a little with adapting Ayeri’s Tahano Hikamu to how I imagine fluent-ish handwriting could look like. The image below marries both endeavors for fun.

The text, which recounts an anecdote from several years ago, when I was still living in my student digs, on deterring one kijetesantakalu ‘raccoon, kinkajou, musteloid’ (the hieroglyph in sitelen pona is most adorable) from taking up residency in an unused chimney more permanently, reads as follows:

sama tomo ale la, tomo mi li jo e tomo palisa pi weka kon pimeja. taso, ilo seli li kepeken ala ona. ni la, kijetesantakalu li open kama. tenpo suno la, ona li len lon insa pi tomo palisa, li lape.

pini pi tenpo esun wan la, open suno la, mi en jan ale pi tomo sama mi li kama sona e ni: kijetesantakalu li lon insa pi tomo palisa. mi mu tawa jan seli tan ni: ona o weka e kijetesantakalu. pilin pi mi ale li ni: ken la, kijetesantakalu li kama pakala lon insa tomo. ante la, ona li ike e tomo. kalama ona pi tenpo pimeja kin li ike tawa jan tomo mi. taso, jan seli li kama la, kijetesantakalu li lon insa ala. jan li kama lukin taso e jaki ona.

tenpo kama poka la, mi mu tawa jan pi weka soweli ike tan ni: kijetesantakalu o ken ala kama lon sewi tomo. jan weka li kama, li pali e ijo pi ken ala lon palisa ale pi telo sewi. sitelen noka kijetesantakalu li lon sinpin tomo. jan weka li pana e ona tawa lukin mi. ijo pi ken ala li pona tawa mi ale, li ike taso tawa kijetesantakalu.

jan tomo wan mi li toki e ni tawa mi: tenpo pimeja kama poka la, kijetesantakalu li alasa sin tawa sewi e sinpin tomo. ona li ken ala la, ona li utala a. kalama li wawa la, lape pi jan tomo mi li pakala. tenpo kama la, kijetesantakalu li kama sin ala.

As usual, there is some leeway in interpretation because semantic spaces per lexeme are broad when you only have a hundred-twenty-odd of them, but what I intended to write is this:

Like all houses, my house possessed a chimney. However, the furnace didn’t use it. So, a raccoon started coming. During the day it hid in the chimney and slept.

One weekend morning, me and my flatmates learned that a raccoon was in the chimney. We called out to the fire department to have it removed. We thought that maybe the raccoon had hurt itself in the chimney. Anyway, it would sully it. Its night-time noise was also annoying to my flatmates. However, when the fire department showed up, the raccoon wasn’t inside. The men only found its droppings.

Soon after, we contacted pest control in order for the raccoon to not get onto the roof. An agent came and installed a blocking device on all rain pipes. Footprints of the raccoon were on the house’s wall. The agent showed them to us. The blocking devices were good for us, though bad for the raccoon.

One of my flatmates told me that the next night, the raccoon again tried to climb the house wall. When it couldn’t, it struggled. The loud noise disrupted my flatmate’s sleep. The raccoon never returned.

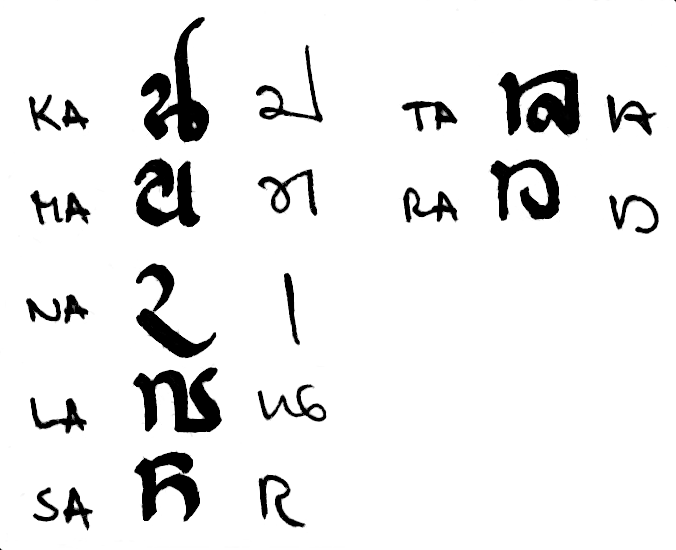

The text in the image above was written with a ball pen on graph paper, as one does—I edited out the lines and am still wondering what would be appropriate writing utensils for my fictional Tahano Hikamu users. Of course, Toki Pona only uses a small subset of my script’s characters and diacritics due to its small phonemic inventory. However, if you compare notes with the Alphabet page and try to decipher the handwriting, you’ll be able to discover that the shapes especially of ka, ma, na, la, and sa have been simplified in comparison to their more formal appearance.

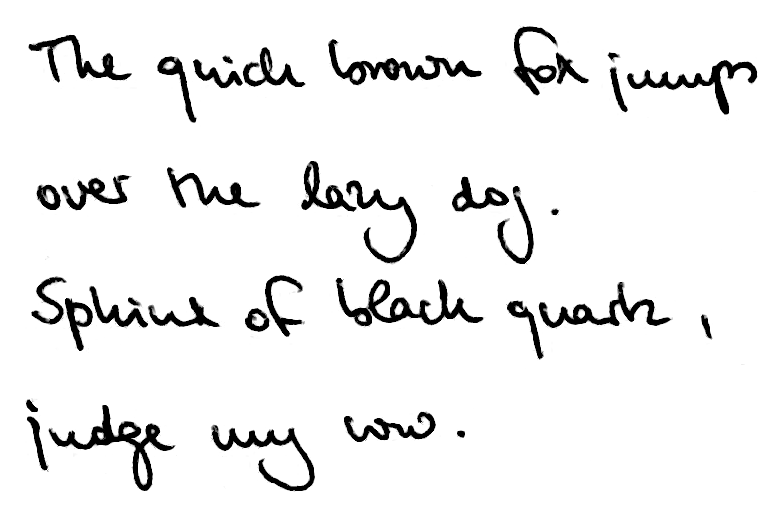

The relative similarity between the ta and ra characters can be disambiguated by making the inside-loop of ta wedge-shaped and the whole character more angular overall. Connecting characters to each other when writing quickly sometimes blurs the difference slightly, though. This isn’t so bad for Toki Pona since it doesn’t have /r/, but it would be noticeable, for instance, in Ayeri. Moreover, there is no clear distinction between pa (like n) and ya (like u) in my handwritten sample above as they both assume a shape like u, which for instance renders jan ‘person’ and pana ‘give, provide, put’ almost indistinguishable but for the dot after the na to mark the omission of a vowel in jan. This is a feature of my ordinary Latin handwriting carrying over, as you can see below. I merge the two shapes there as well with usually no ill effects because context clarifies the intended reading.

After all, you normally don’t read words letter by letter if you’re familiar with both the script and the language it spells. In Toki Pona’s case specifically, there are only so few possible candidates due to the paucity of lexemes, anyway. I imagine, a native Tahano Hikamu user of whatever language background wouldn’t have too much difficulty either.

Post scriptum

The only consonant that can end a syllable in Toki Pona is /n/, so I guess it would make sense in those cases to use the

kijetesantakalu on behalf of the -n + t- cosonant cluster (it looks like ʀ̩ to spell saN). It’s not a big stretch to extend its use to indicate a nasal coda consonant in general. (2024-10-12)