In this series of blog articles—taken (more or less) straight from the current working draft of chapter 5.4 of the new grammar for better visibility and as a direct update of an old article (“Flicking Switches: Ayeri and the Austronesian Alignment”, 2012-06-27)—I will finally reconsider the way verbs operate with regards to syntactic alignment.

All articles in this series: Typological Considerations · ‘Trigger Languages’ · Definition of Terms · Some General Observations · Verb agreement · Syntactic Pivot · Quantifier Float · Relativization · Control of Secondary Predicates · Raising · Control · Conclusion

Verbs govern the relations of the various phrase types to each other and they are thus central to the formation of clauses. Just from looking at the numerous examples given both on this website and in the grammar, it should be clear that Ayeri’s preferred word order is verb-first, which opens up a few typological questions—first and foremost, whether Ayeri actually has a verb phrase, or in terms of generative grammar: whether it is configurational in this regard. Ayeri definitely has a constituent structure as far as NPs, APs, PPs, etc. are concerned. However, due to VSO word order, it is not obvious whether verb and object actually form a VP constituent together, since V and O are not adjacent to each other. Since Ayeri marks topics in terms of morphology, it will also be necessary to discuss how this mechanism works and how it relates to the notion of the subject.

A discussion of subject, topic, and configurationality is interesting also in that Ayeri’s syntactic alignment was originally inspired by the Austronesian or Philippine alignment system, though then under the term ‘trigger language’ which is itself not unproblematic. Tagalog, an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian branch, spoken mainly in the Philippines (Hammarström et al. 2017: Tagalog; Schachter and Otanes 1972), usually serves as the academic poster child in descriptions of Austronesian alignment. Ayeri departs from Tagalog’s system in a number of ways, though, and probably towards the more conventional. Austronesian alignment is not necessarily the best model to liken Ayeri’s syntax to. It will nonetheless be informative to compare both systems based on the work of Kroeger (1991, 1993), who provides an analysis of Tagalog’s syntactic alignment roughly in terms of the LFG framework and describes some heuristics which may be helpful in establishing what is actually going on in Ayeri. As mentioned in a previous blog article (“Happy 10th Anniversary, Ayeri”, 2013-12-01), I started Ayeri in late 2003—then still in high school and not knowing much about linguistics. Of course, I had to go and pick as a model the one alignment system which has long been “a notorious problem for both descriptive grammarians and theoretical syntacticians” to the point where it “sometimes seems as if Austronesian specialists can talk (and write) of nothing else” (Kroeger 2007: 41).

As mentioned above, Ayeri’s unmarked word order gives the verb first, and then, in decreasing order of bondedness to the verb, the phrases which make up the verb’s arguments: subject (agent), direct object (patient), indirect object (dative), followed by adverbials in the genitive, locative, instrumental, and causative case. Ayeri’s basic word order is thus VSO, a trait it has in common with about

-

- Order of subject, object and verb: VSO

- Order of verb and object: VO

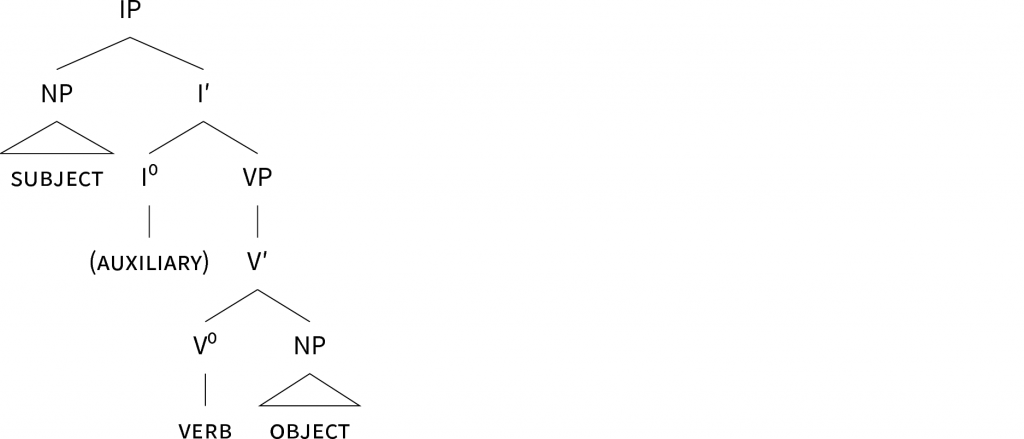

It is commonly assumed that languages have a subject which occupies a certain position in the constituent structure which commands a constituent jointly formed by the verb and its dependents—the predicate. An SVO sentence in English thus very generally looks like in (2) (compare the examples in Bresnan et al. 2016: 101–111).

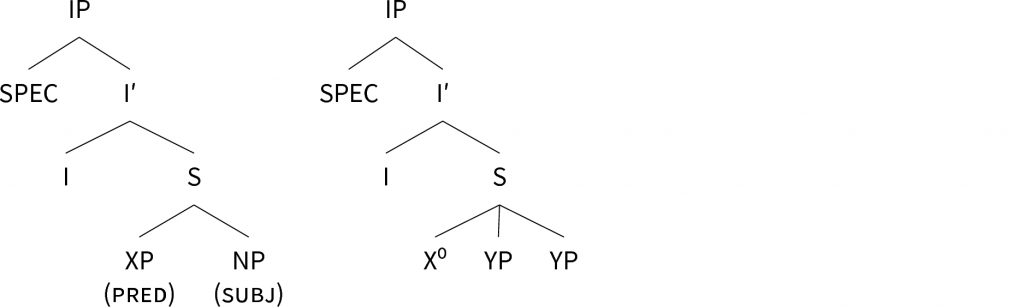

However, Ayeri is a VSO language, so the question arises how the basic constituent structure should be diagrammed in tree form, since V and O are not adjacent. As an initial hypothesis one might assume that they cannot form a unit together, since S somehow stands in between the constituents it is supposed to command. A very first stab at diagramming would probably be to come up with a flat, non-configurational structure, all but lacking a VP, as shown in (3).

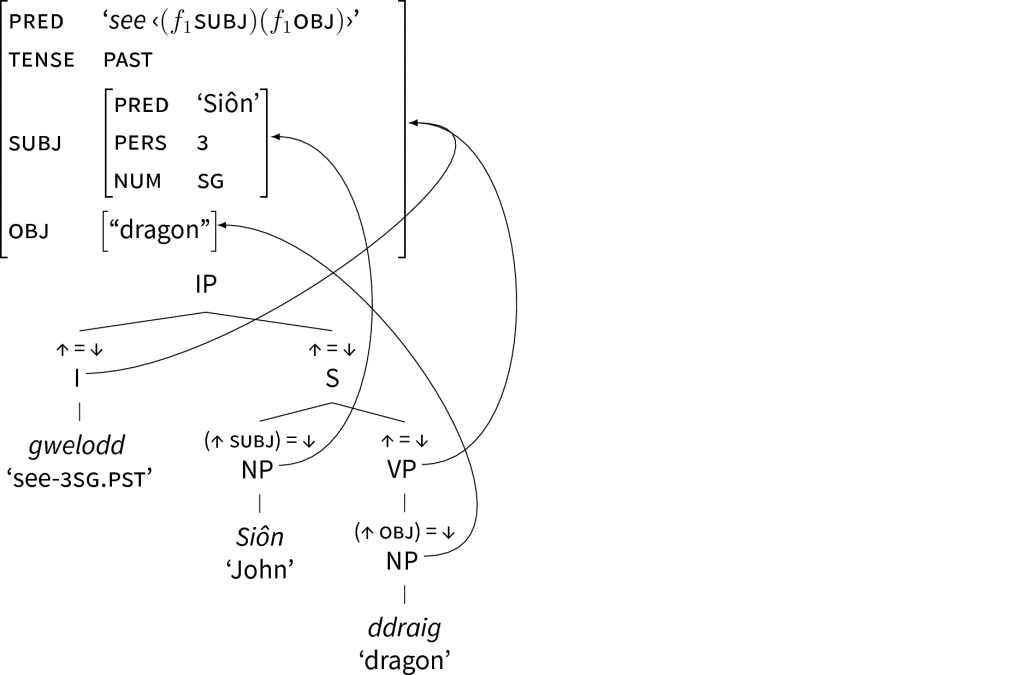

Such a structure, though, does not do Ayeri justice in that, for instance, right-node-raising of a subject and object NP together is possible, so there is evidence that they form a constituent subordinate to the verb. NP–XP constructions where XP is not a maximal projection of a verb also exist in isolation, so NP and XP are probably contained in a small-clause constituent S separate from the verb. The verb in the initial position furthermore shows inflection, so one might rather construe it as an I⁰, projecting an IP, which frees up VP for other purposes while we can use IP to govern both Iʹ and S. In fact, such a structure is basically the conclusion Chung and McCloskey (1987) come to for Irish, which is also a VSO language (4a). Bresnan et al. (2016) give the chart in (4b) for Welsh, equally a VSO language (also compare Dalrymple 2001: 66, sourcing Sadler 1997). Kroeger (1991) suggests the two structures depicted in (4c) for Tagalog, based on the suggested constituent structure for Celtic languages.

What all of these c-structures have in common is that the inflected verb appears in I⁰, which is a sister of S. S, in turn, is a small clause containing the arguments of the verb. In the cases of Irish and Welsh, however, there is a VP sister of the subject NP which itself does not have a head, but contains the object NP as a complement. In the case of Tagalog, S is non-configurational, that is, while XP may contain a non-finite verb, the subject and object NPs are on equal footing.

Bresnan et al. (2016: 129–138) inform that the phenomenon of the verb ending up in a different head position (V⁰ apparently moves to I⁰) in (4b) is commonly known as ‘head movement’, except that LFG is built specifically without any movement. Since LFG is based on the assumption that all nodes in a syntactic structure are base-generated, that is, that there are no transformational rules generating the surface structure from a deeper layer of representation underneath it, there cannot be a trace of V left behind in VP. LFG avoids empty categories, as there is no information contained in an empty node. The functional information provided by the verb is not lost, however, it is merely now provided by the verb in I⁰. Essentially, the Welsh example does not violate endocentricity, since the finite verb in I⁰ still forms the verbal head in the functional structure representation of the clause. With regards to constituent structure, V⁰, if present, c-commands its NP sister; both V⁰ and NP are dominated by VP:

-

- Exhaustive domination (Carnie 2013: 121):

“Node A exhaustively dominates a set of terminal nodes {B, C, …, D}, provided it dominates all the members of the set so that there is no member of the set that is not dominated by A and there is no terminal node G dominated by A that is not a member of the set.”

- C-command (Carnie 2013: 127):

“Node A c-commands node B if every node dominating A also dominates B, and neither A nor B dominates the other.”

- Exhaustive domination (Carnie 2013: 121):

The AVM in (4b) shows that the contents normally found in V⁰ are provided by the head of its equivalent functional category, I⁰. I⁰ and VP are said to map into the same f-structure (Bresnan et al. 2016: 136). Endocentricity still holds in that IP dominates all nodes below it, thus also I⁰ and the object NP. In addition, I⁰ c-commands its sister node and all of its children, hence also the object NP. As Bresnan et al. (2016) put it: “X is an extended head of Y if X is the Xʹ categorial head of Y […], or if Y lacks a categorial head but X is the closest element higher up in the tree that functions like the f-structure head of Y” (136). For our example, replace X with I⁰ and Y with VP in the second half of the quote: I⁰ is the closest element higher up in the tree that functions like the f-structure head of VP, which itself lacks a categorial head.

The analysis of the sentence structure of Celtic languages shows that VSO languages do not automatically need to be considered ‘non-configurational’ and lacking a VP if the notion of extended heads is accepted. In any case, tests need to be performed to see whether one of the analyses presented in (4) holds true for Ayeri as well. However, this will not be in the scope of this series of blog articles.

- Bresnan, Joan et al. Lexical-Functional Syntax. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2016. Print. Blackwell Textbooks in Linguistics 16.

- Carnie, Andrew. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2013. Print. Introducing Linguistics 4.

- Chung, Sandra, and James McCloskey. “Government, Barriers, and Small Clauses in Modern Irish.” Linguistic Inquiry 18.2 (1987): 173–237. Web. 11 Aug. 2017. ‹http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178536›.

- Dalrymple, Mary. Lexical Functional Grammar. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 2001. Print. Syntax and Semantics 34.

- Dryer, Matthew S. “Order of Subject, Object and Verb.” The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Eds. Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. 2013. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, n.d. Web. 11 Aug. 2017. ‹http://wals.info/chapter/81›.

- Hammarström, Harald et al., eds. “Language: Tagalog.” Glottolog. Version 3.0. Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, n.d. Web. 11 Aug. 2017. ‹http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/taga1270›.

- Kroeger, Paul R. Phrase Structure and Grammatical Relations in Tagalog. Diss. Stanford University, 1991. Web. 17 Dec. 2016. ‹http://www.gial.edu/wp-content/uploads/paul_kroeger/PK-thesis-revised-all-chapters-readonly.pdf›.

- ———. “Another Look at Subjecthood in Tagalog.” Pre-publication draft. Philippine Journal of Linguistics 24.2 (1993): 1–16. Web. ‹http://www.gial.edu/documents/Kroeger-Subj-PJL.pdf›

- ———. “McKaughan’s Analysis of Philippine Voice.” Piakandatu ami Dr. Howard P. McKaughan, 41–. Eds. Loren Billings and Nelleke Goudswaard. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines and SIL Philippines, 2007. Print.

- Sadler, Louisa. “Clitics and the Structure-Function Mapping.” Proceedings of the LFG ’97 Conference, University of California, San Diego, CA. Eds. Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications, 1997. Web. 12 Aug. 2017. ‹https://web.stanford.edu/group/cslipublications/cslipublications/LFG/2/lfg97sadler.pdf›.

- Schachter, Paul and Fe T. Otanes. 1972. Tagalog Reference Grammar. Berkeley: U of California P, 1983. Google Books. Google, 2011. Web. 6 Nov. 2011. ‹http://books.google.com/books?id=E8tApLUNy94C›.